If there were any doubts that Wall Street’s long-awaited rebound in initial public offerings is here, they were put to rest this past week.

Six companies went public over five days that each raised more than $100 million — something that hasn’t happened since November 2021, according to Renaissance Capital. Collectively, IPOs from these companies raised $4.4 billion.

“The pickup is here,” Renaissance Capital director of investment strategies Avery Marquez said in an interview, adding, “Things could change very quickly. Right now, it looks like we’re in for a very active fall.”

The action pushed total proceeds from all traditional IPOs so far this year to $25 billion, according to Dealogic, which is also the highest since 2021.

The new offerings include a Swedish buy now, pay later lender, a blockchain platform that approves mortgages, a Pacific Northwest coffee bar chain, and a crypto exchange started by billionaire twins Tyler and Cameron Winklevoss.

Renaissance isn’t expecting another five-day stretch to match that number of big deals, which is defined as more than $100 billion. Currently, it’s projecting about three to five such IPOs per week for the next two months.

This past week ended with Friday listings from Gemini Space Station (GEMI), the parent company of crypto exchange Gemini; coffee chain Black Rock Coffee Bar (BRCB); transportation software company Via Transportation (VIA); and building efficiency provider Legence (LGN).

Gemini raised $425 million in its IPO. The crypto exchange’s stock was up 18% as of Friday afternoon. Black Rock Coffee Bar, Via, and Legence raised $294 million, $493 million, and $728 million, respectively. Their stocks are up 45%, 3%, and 8%, respectively.

“IPO issuance has exploded post Labor Day,” Bank of America head of Americas equity capital markets Jim Cooney said. He noted that IPO road shows held by senior executives and their bankers are currently the busiest they’ve been since the peak of IPO mania in mid-2021.

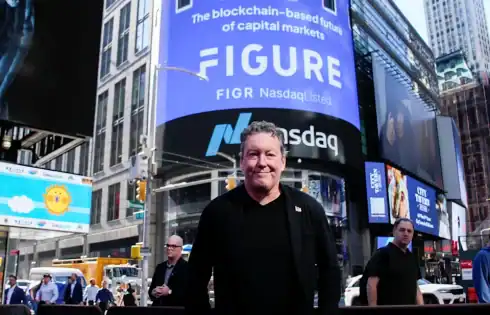

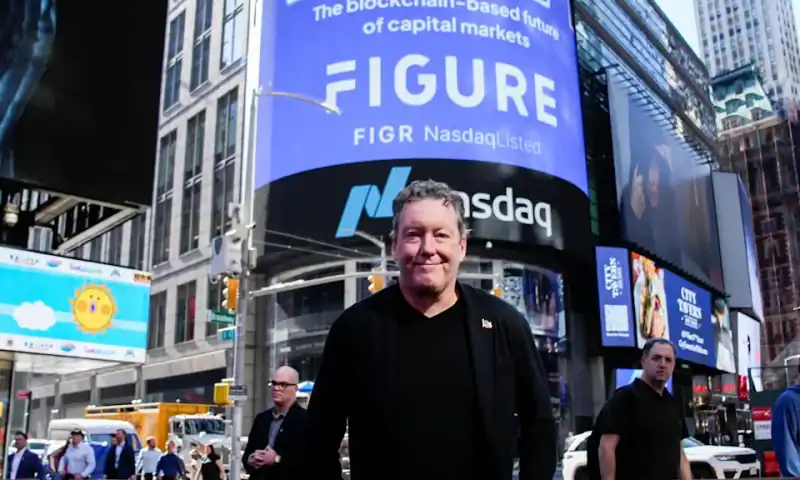

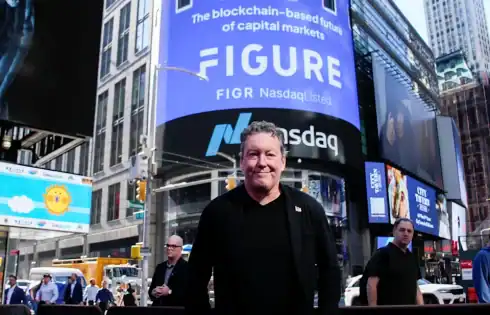

Earlier in the past week came public listings from buy now, pay later lender Klarna (KLAR) and Figure Technology Solutions (FIGR), a blockchain platform that offers crypto trading and a marketplace for mortgages.

Figure and Klarna raised $787.5 million and $1.37 billion, respectively, in their public listings. Their stocks were up 7% and down 3%, respectively, as of Friday afternoon.

Mike Cagney, Figure co-founder and former CEO of SoFi Technologies (SOFI), told Yahoo Finance Thursday that the company plans to use the fresh capital “like a weapon” to outcompete rivals.

“Having that balance sheet is going to allow us to lean in and really push disruptive blockchain use cases in a way that not having that capital would be difficult,” Cagney said.

With most of his wealth tied up in Figure shares, Cagney is now a billionaire thanks to his company’s IPO, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index.

Not everyone is viewing the return of IPO mania this week with excitement. While their Wall Street operations appear to be humming, some major bankers pointed out more uncertainty when looking at the full economic picture.

“Risk appetite is definitely out on what I’d say is the more exuberant end of the spectrum,” Goldman Sachs CEO David Solomon said Monday.

“We’re looking at the back half [of the year] to likely have slowing growth, in 2026 to have slowing growth as well,” Citigroup CFO Mark Mason said Tuesday.

A report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics on Tuesday showed that the US added nearly a million fewer jobs than initially reported in the monthly payroll report for the 12-month period ending in March 2025. The massive revision came only days after the preliminary payroll report showed that the US added just 22,000 jobs in August.

Uncertainty “kind of just seems like something that’s on everybody’s mind, but not really influencing their risk appetites,” Renaissance’s Marquez added.

A virtual pet that only comes alive when two people raise it together is at the center of a growing AI movement out of Berlin.

Born, an AI gaming startup co-founded and led by Fabian Kamberi, announced on Sept. 10 that it just secured $15 million in a Series A round led by Accel with backing from Tencent and Laton Ventures, lifting its total funding to $25 million.

A virtual pet that only comes alive when two people raise it together is at the center of a growing AI movement out of Berlin.

Born, an AI gaming startup co-founded and led by Fabian Kamberi, announced on Sept. 10 that it just secured $15 million in a Series A round led by Accel with backing from Tencent and Laton Ventures, lifting its total funding to $25 million.

David Rosenberg isn’t always right. The founder of Rosenberg Research, who rose to fame after calling the 2008 recession, regularly expresses a bearish outlook for the economy and markets that often don’t come to fruition.

But in a world where bullish forecasts are the consensus among Wall Street’s top equity strategists, it can be prudent to heed Rosenberg’s warnings. While his predictions usually don’t play out, there’s no denying that the economist sufficiently shows his work, providing relevant data that ought to give investors pause.

In a recent note to clients, Rosenberg provided some concerning numbers on where the S&P 500’s forward returns could be headed, given current valuations.

The index’s Shiller cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio is hovering around 37.5. The measure smooths out business cycles by comparing current stock prices to a 10-year rolling average of earnings.

It’s the third-most expensive level of all-time, behind peaks in 2021 and 2022.

David Rosenberg isn’t always right. The founder of Rosenberg Research, who rose to fame after calling the 2008 recession, regularly expresses a bearish outlook for the economy and markets that often don’t come to fruition.

But in a world where bullish forecasts are the consensus among Wall Street’s top equity strategists, it can be prudent to heed Rosenberg’s warnings. While his predictions usually don’t play out, there’s no denying that the economist sufficiently shows his work, providing relevant data that ought to give investors pause.

In a recent note to clients, Rosenberg provided some concerning numbers on where the S&P 500’s forward returns could be headed, given current valuations.

The index’s Shiller cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio is hovering around 37.5. The measure smooths out business cycles by comparing current stock prices to a 10-year rolling average of earnings.

It’s the third-most expensive level of all-time, behind peaks in 2021 and 2022.