The European Union has introduced a new mechanism for screening foreign investment.

It’s widely believed to have been prompted by concerns over China’s economic ambitions in Europe.

It will allow the European Commission – the EU’s executive arm – to give an opinion when an investment “threatens the security or public order” of more than one member state or undermines an EU-wide project such as the Galileo satellite project.

In March, the European Commission called China a “systemic rival” and a “strategic competitor”.

The Chinese Ambassador to the EU urged the bloc to remain “open and welcome” to Chinese investment, and not to “discriminate”.

How much foreign investment is in the EU?

China’s ownership of EU businesses is relatively small, but has grown quickly over the past decade.

A third of the bloc’s total assets are now in the hands of foreign-owned, non-EU companies, according to a report from the European Commission in March.

Of these, 9.5% of companies had their ownership based in China, Hong Kong or Macau – up from 2.5% in 2007.

That compares with 29% controlled by US and Canadian interests by the end of 2016 – down from nearly 42% in 2007.

So, it’s a significant increase, but the total amount is not huge, comparatively speaking.

China in the EU

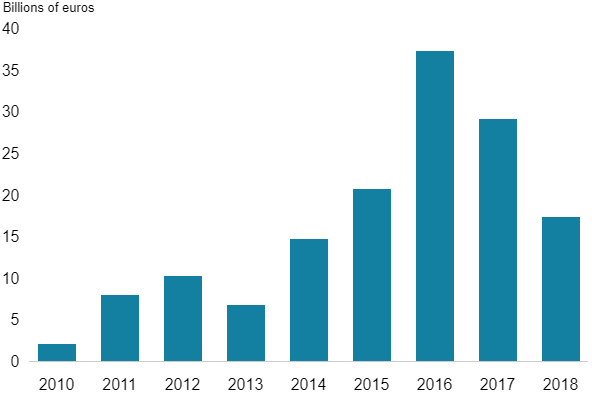

Foreign direct investment into the 28 member states

Although the levels of Chinese foreign direct investment in the EU have been increasing rapidly, it peaked at €37.2bn in 2016 amidst a slowdown in Chinese investment globally, according to the Rhodium Group and the Mercator Institute for China Studies.

In European countries outside the EU, investment also dropped in 2018.

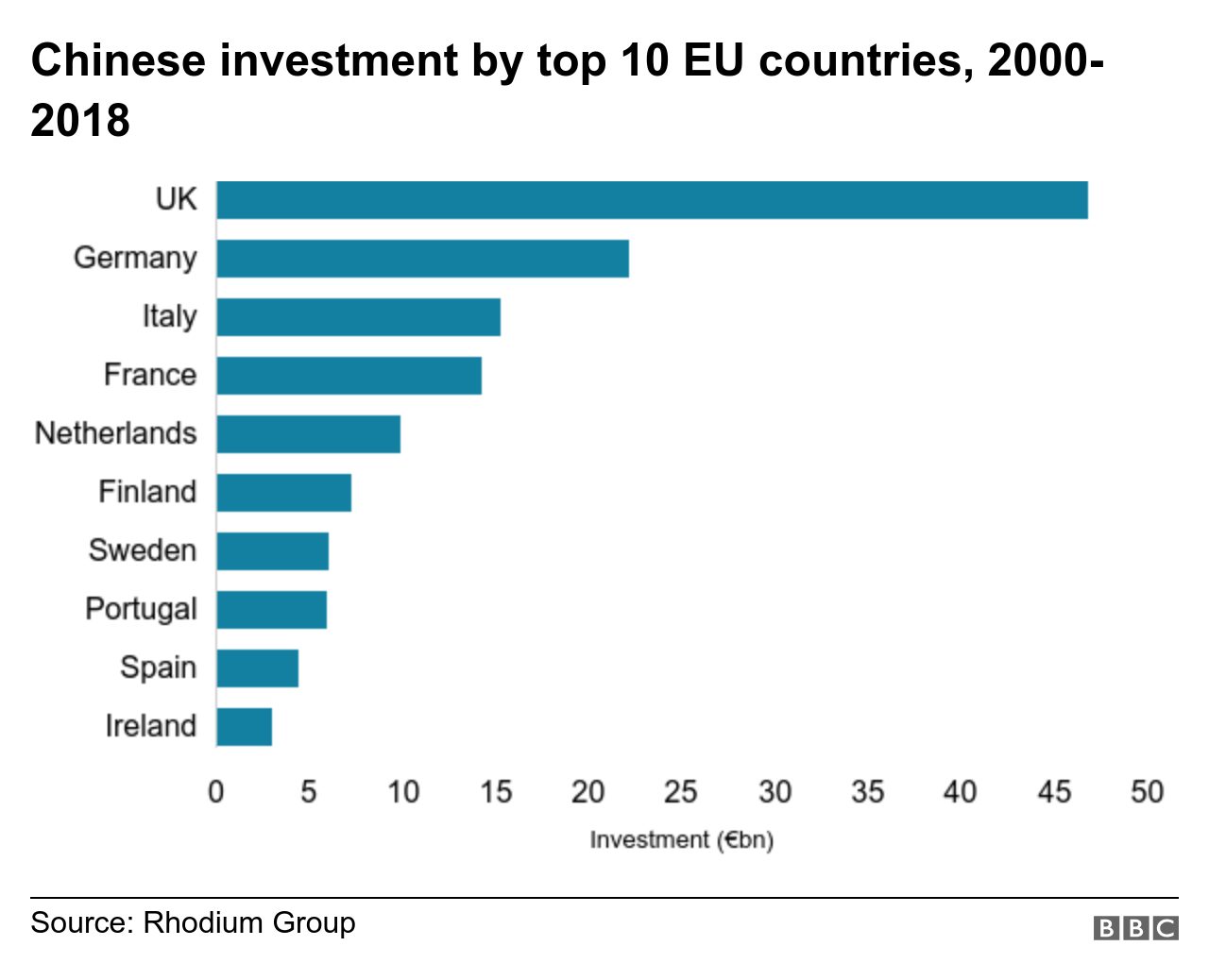

What and where is China investing?

A large proportion of Chinese direct investment, both state and private, is concentrated in the major economies, such as the UK, France and Germany combined, according to the Rhodium Group and Mercator Institute.

Analysis by Bloomberg last year said that China now owned, or had a stake in, four airports, six maritime ports and 13 professional soccer teams in Europe.

It estimated there had been 45% more investment activity in 30 European countries from China than from the US, since 2008.

And it said this was underestimating the true extent of Chinese activity.

What about infrastructure?

In March, Italy was the first major European economy to sign up to China’s new Silk Road programme – known as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

It involves huge infrastructure building to increase trade between China and markets in Asia and Europe.

Officially more than 20 countries in Europe (including Russia) are part of the initiative.

For example, China is financing the expansion of the port of Piraeus in Greece and is building roads and railways in Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia-Herzegovina and North Macedonia.

This could prove attractive to poorer Balkan and southern European countries, especially as demands for transparency and good governance can make EU funding appear less attractive.

However, analysts point out that Chinese loans come with conditions – such as the involvement of Chinese companies – and also risk burdening these countries with large amounts of debt.

Will Chinese investment grow?

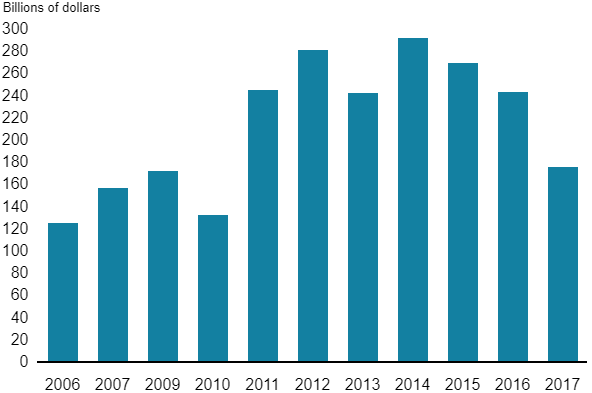

Globally, China’s outward direct investment has slowed over the last year or two, after more than a decade of expansion.

“This is mainly the result of stricter controls on capital outflows from China, but also of a changing political environment globally concerning Chinese investment,” says Agatha Kratz of the Rhodium Group.

China’s global investment slows

Total investment outflows (FDI)

The Trump administration is taking a tougher line towards China’s economic activities.

Governments elsewhere are more cautious – particularly when it comes to investment in sensitive areas of the economy, such as telecommunications and defence.

But there’s little doubt China is now a significant player in Europe, whether through direct investments or via the new Silk Road project.