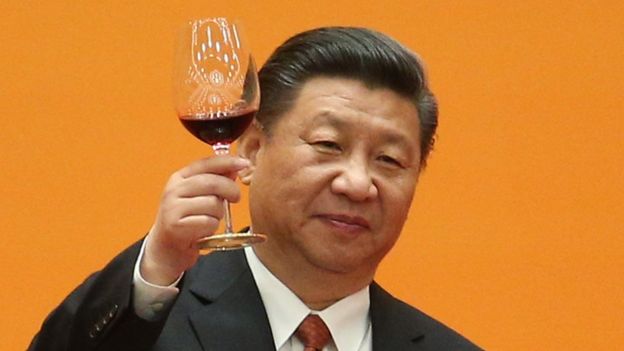

China’s president lands in Rome on Thursday, where he is expected to sign a landmark infrastructure deal that has raised eyebrows and suspicions among Italy’s Western allies.

Xi Jinping’s project is a New Silk Road which, just like the ancient trade route, aims to link China to Europe.

The upside for Italy is a potential flood of investment and greater access to Chinese markets and raw materials.

But amid China’s growing influence and questions over its intentions, Italy’s Western allies in the European Union and United States have concerns.

By land and by sea

The New Silk Road has another name – the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – and it involves a wave of Chinese funding for major infrastructure projects around the world, in a bid to speed Chinese goods to markets further afield. Critics see it as also representing a bold bid for geo-political and strategic influence.

It has already funded trains, roads, and ports, with Chinese construction firms given lucrative contracts to connect ports and cities – funded by loans from Chinese banks.

The levels of debt owed by African and South Asian nations to China have raised concerns in the West and among citizens – but roads and railways have been built that would not exist otherwise:

- In Uganda, Chinese millions built a 50km (30 mile) road to the international airport

- In Tanzania, a small coastal town may become the continent’s largest port

- In Europe too, Chinese firms managed to buy 51% of the port authority in Piraeus port near Athens in 2016, after years of economic crisis in Greece

Italy, however, will be the first top-tier global power – a member of the G7 – to take the money offered by China.

It is one of the world’s top 10 largest economies – yet Rome finds itself in a curious situation.

The collapse of the Genoa bridge in August killed dozens of people and made Italy’s crumbling infrastructure a major political issue for the first time in decades.

And Italy’s economy is far from booming.

The country slipped into recession at the end of 2018, and its national debt levels are among the highest in the eurozone. Italy’s populist government came to power in June 2018 with high-spending plans but had to peg them back after a stand-off with the EU.

It is in this context that China’s deal is being offered – funding that could rejuvenate Italy’s grand old port cities along the Maritime Silk Road.

Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte has mentioned the cities of Trieste and Genoa as likely candidates.

“The way we see it, it is an opportunity for our companies to take the opportunity of China’s growing importance in the world,” said Italy’s undersecretary of state for trade and investment, Michele Geraci.

“We feel that amongst our European partners, Italy has been left out. We have wasted a little bit of time,” he told the BBC.

So what’s in it for China?

Italy’s move is “largely symbolic”, according to Peter Frankopan, professor of Global History at Oxford University and a writer on The Silk Roads.

But even Rome admitting the BRI is worth exploring “has a value for Beijing”, he said.

“It adds gloss to the existing scheme and also shows that China has an important global role.”

“The seemingly innocuous move comes at a sensitive time for Europe and the European Union, where there is suddenly a great deal of trepidation not only about China, but about working out how Europe or the EU should adapt and react to a changing world,” Prof Frankopan told the BBC.

“But there is more at stake here too,” he added. “If investment does not come from China to build ports, refineries, railway lines and so on, then where will it come from?”

Ahead of his arrival, President Xi declared that the friendship between the two nations was “rooted in a rich historical legacy”.

“Made in Italy has become synonymous with high quality products. Italian fashion and furnishings fully meet the taste of Chinese consumers; pizza and tiramisu are liked by young Chinese people,” he wrote in an article published by Corriere della Sera.

That “made in Italy” label carries a reputation for quality worldwide, and is legally protected for products items processed “mainly” in Italy.

In recent years, Chinese factories based in Italy using Chinese labour have been challenging that mark of quality.

Better connections for cheap raw materials from China – and the return of finished products from Italy – could exaggerate that practice.

“Predatory” investment

The non-binding deal being signed by the two countries on Thursday comes amid questions over whether Chinese firm Huawei should be permitted to build essential communications networks – after the United States expressed concern they could help Beijing spy on the West.

That is not part of the current negotiations in Italy.

But a little over a week before the deal was due to be signed, the European Commission released a joint statement on “China’s growing economic power and political influence” and the need to “review” relations.

As President Xi tours Rome, EU leaders in Brussels will be considering 10 points for relations with China.

While they include deepening engagement, they also involve plans to “address the distortive effects of foreign state ownership” as well as “security risks posed by foreign investment in critical assets, technologies and infrastructure”.

In March, US National Security Council spokesman Garrett Marquis pointed out that Italy was a major economy and did not need to “lend legitimacy to China’s vanity infrastructure project”.

Members of Italy’s ruling right-wing League party have their owns concerns about national security

Interior Minister Matteo Salvini warned that he did not want to see foreign businesses “colonising” Italy.

“Before allowing someone to invest in the ports of Trieste or Genoa, I would think about it not once but a hundred times,” Salvini warned.

Setting the scene

Italian officials are keen to point out that the deal being signed is not an international treaty, and is non-binding.

“There are no specific projects,” Mr Geraci said. “It is more of an accord that sets the scene.”

Other European nations already accept Chinese investment through something called the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, he said – something the UK was the first to sign up to.

“And then one by one, France, Germany, Italy and everyone else also followed suit,” Mr Geraci said.

Similarly, he believes Italy’s neighbours will soon follow it into the Belt and Road initiative.

“I do believe that this time Italy is actually leading Europe – which I understand may be a surprise to most,” he added.