There’s reason to hope — really

Don’t give up on international stocks.

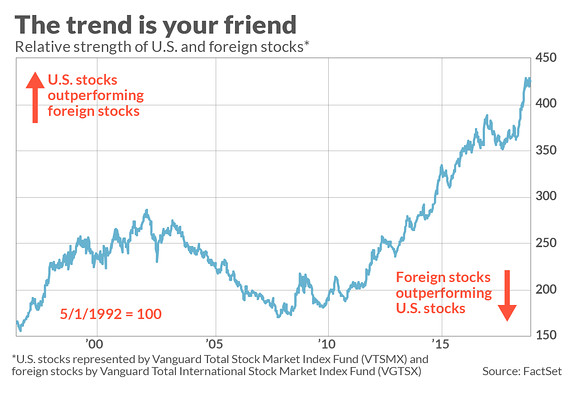

I concede that retirees have been hearing that advice for many years now, and have little to show for it. Over the last five years, for example, U.S. stocks have beaten international stocks by an annualized margin of 8.0 percentage points (as measured by the Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund VTSMX, -3.32% and the Vanguard Total International Stock Market Fund VGTSX, -2.08% ). U.S. stocks’ margin of victory over the last decade comes to 6.7 annualized percentage points. These are huge differences.

But there’s reason to hope—really. The only real reason to give up would be if you think that “this time is different.”

Consider what I found upon feeding into my PC’s statistical package the calendar-year returns since 1970 for the S&P 500 and MSCI’s Europe Australasia and Far-East (EAFE) Index. I chose the EAFE index because it is the international equity benchmark for which data extends back the furthest. When looking at year-to-year patterns, I came up empty: There is no statistically significant correlation from one year to the next in their relative strength.

To be sure, there is modest year-to-year momentum. That is, S&P 500 SPX, -3.24% relative strength over EAFE in a given year is more likely to be repeated in the subsequent year than to be reversed. But this tendency is not strong enough to satisfy a statistician at the 95% confidence level.

As we expand our holding period to longer and longer periods, however, statistical significance begins to show up in the data. And the pattern is a contrarian one, just the opposite of momentum. That is, after a long-enough period in which one of the two asset classes dominates, chances grow that the situation is likely to reverse.

How long? It’s hard to be precise, since robust data for the performance of international stocks extends back only about five decades or so. That’s insufficient to allow us to draw robust statistical conclusions.

But it certainly appears that five years is not long enough to increase the odds of a reversal. But as you extend the holding period beyond that, however, those odds begin to grow.

This is illustrated in the accompanying chart, which shows the relative strength of U.S. and international stocks over the last 20 years. Notice the long waves—multiyear periods in which one or other of these two categories dominates the other: For example, from 1996-2002, when U.S. stocks exhibited relative strength, and from 2002-2008, when it was the other way around. A similar pattern emerges in previous decades as well.

What this means for today: Since U.S. stocks have been outperforming international stocks for 10 years, odds are high and growing that the situation will soon reverse itself.

This conclusion gets even more support when considering valuations. As is well known, U.S. equities are overvalued by almost any measure. International stocks are much less expensive, both relative to U.S. equities but, in many cases, in absolute terms as well. Only if you believe that valuations no longer matter would you project that U.S. stocks’ relative strength over the last decade will last forever.

To be clear, however, there are no guarantees. The arguments summarized here could for the most part have been made a year or two ago and, at least so far, U.S. stocks have continued to dominate. This is why most retirement planners recommend that we diversify our equity holdings among both U.S. and international stocks, rather than make specific market timing bets on which will be stronger in a given year.

Right now, for example, U.S. stocks on a market-cap basis represent about half of the world’s total equity market. So the most neutral bet would be to divide your equity holdings half and half between domestic and international. Any deviation from that fifty-fifty split would in essence be a bet that U.S. stocks will outperform international stocks, or vice versa.

Chances are that you already have a sizable allocation to international equities. If so, the investment implication of this discussion is, that even if you choose not to increase that allocation, at a minimum you should not give up on what you already have.