While this year’s sharp selloff in stocks might feel brutal, particularly after the carnage of September, the S&P 500 remains about 17.1% above year-end 2019 levels, according to Dow Jones Market Data.

That isn’t low enough, given the likely scope of Federal Reserve actions needed to bring surging inflation back to the central bank’s 2% annual target, according to Steven Blitz, chief U.S. economist at TS Lombard.

“Yes, markets are being routed, but, to date, they are resetting from too rich price levels created by Fed policies that went on way too long,” Blitz said in recent client note.

“Financial conditions are consequently tightening but are not yet enough to

justify concerns the economy is about to blow a gasket.”

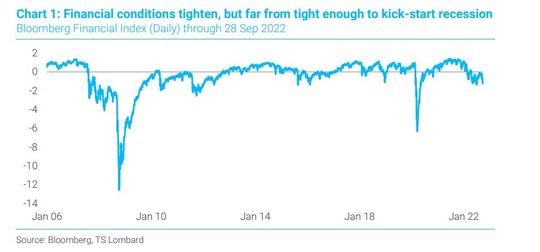

Blitz pointed to how little financial conditions have tightened (see chart) relative to past recessions, to bolster his case for why the Fed still needs to raise its policy rate by more than anticipated.

U.S. stocks ended lower Wednesday in choppy trade, after rallying sharply to kick off October and following their worst September since 2002. William Watts wrote how after a harsh September, the S&P 500’s SPX, -0.20% typically sees modest gains a month later, but not the Dow Jones Industrial Average, DJIA, -0.14% when looking at historical data.

The main problem, for Blitz, is that this year’s stock-market decline has been “hardly a shakeout” when looking at the roughly 50% drop in equities in the 1974-75 recession and the one in 2008-09.

“More to the point, the market has gotten here by pricing in the Fed’s 4.5% solution (4.5% inflation, 4.5% unemployment, 4.5% funds rate) with all believing this

will be enough to put maximum downward pressure on inflation,” Blitz said. “It won’t.”

Investors have been focusing on Friday’s jobs report for September for clues as to whether the Fed might keep up its pace of outsize rate hikes in the face of robust wage gains that have been fueling inflation.

Instead, Blitz estimates the Fed “solution” might need to hit 5.5%, particularly with household balance sheets remaining resilient so far, even as interest rates have dramatically climbed, which has cooled the housing market as the 30-year fixed mortgage rate nears 7%.

Energy costs as a component of inflation came back into focus Wednesday as crude prices rose after major oil producers agreed to reduce their collective crude production levels by 2 million barrels a day, starting next month.

The decision was followed by the U.S. benchmark West Texas Intermediate crude for November delivery CLX22, 0.27% CL00, 0.27% gaining 1.4% at $87.76 a barrel.

U.S. crude prices have tumbled from an peak intraday high in March of almost $130 a barrel, according to FactSet data, after they surged as global economies first emerged from pandemic lockdowns, but also as the move to greener power sources gathered steam and from Russia’s war in Ukraine.