Hay bales in flames, manure dumped on highways, blockades at supermarket distribution centres and demonstrations on politicians’ doorsteps.

Dutch farmers have been generating global headlines with protests described by Prime Minister Mark Rutte as “wilfully endangering others, damaging our infrastructure and threatening people who help with the clean-up”.

This proud farming nation is under immense pressure to make radical changes to cut harmful emissions, and some farmers fear their livelihoods will be obliterated.

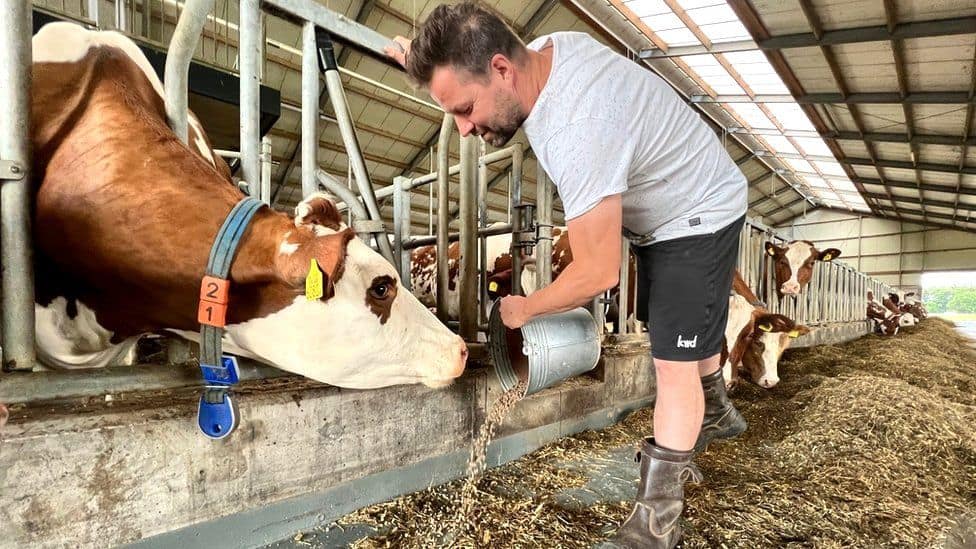

“It’s in our blood, I want to do this, and if we have to adapt to new situations, I want to, but we have to be fair, it takes time – give me a chance,” says Geertjan Kloosterboer, a third-generation dairy farmer.

We are standing in his recently built barn, surrounded by red and white cows, as his eldest son sweeps past us on a small digger.

I ask if Geertjan sees a future for his children in farming.

“I don’t know if that’s what they want. When we talk about farming it’s just stress. But I want them to have a choice, not for the government to make that choice for them.”

Dutch government proposals for tackling nitrogen emissions indicate a radical cut in livestock – they estimate 11,200 farms will have to close and another 17,600 farmers will have to significantly reduce their livestock.

Other proposals include a reduction in intensive farming and the conversion to sustainable “green farms”.

As such, the relocation or buyout of farmers is almost inevitable, but forced buyouts are a scenario many hope to avoid.

The cabinet has allocated €25bn (£20bn) to slicing nitrogen emissions within the farming industry by 2030, and the targets for specific areas and provinces have been laid out in a colour-coded map.

By July 2022 the provincial governments must submit their ideas for hitting those goals – but a handful of provinces have hinted they will not play ball.

‘We need insects’

Biodiversity is under threat. Native species are disappearing more rapidly here than elsewhere in Europe, according to the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency.

Rudi Buis, a representative from the ministry of agriculture, tells me the stakes are high: “It’s necessary to improve the nature, for our health, for clean air, water, soil and also for the agriculture because we need biodiversity. We need insects for our crops… if we want some economic activity in the future, we also have to improve our nature.”

In May 2019, the Council of State ruled the government’s strategy for reducing excess nitrogen breached EU directives on preserving vulnerable habitats.

The judgment meant every activity that led to nitrogen being emitted, from building new homes to farming, required a permit.

Pinning hopes on technology

Agriculture is accountable for nearly half of Dutch nitrogen emissions.

Ammonia (nitrogen and hydrogen, or NH3) comes from manure mixed with urine, and when this washes away into ditches, rivers and the sea, it can be harmful to nature.

Nitrogen oxides (nitrogen and oxygen, NOx) are mainly produced when fossil fuels are burned – traffic, aviation, shipping and industry all contribute.

Plans are also afoot to reduce pollution around Amsterdam’s Schiphol airport, the port of Rotterdam, on roads and in households.

Meanwhile, many are pinning their hopes on technological solutions.

Already, air scrubbers and excrement-sweeping robots operate in barns, while sloping floors are encouraged to reduce contact between the manure and urine – but in most cases they still meet in the cellar.

Diluting manure with water or acidifying it, leaving cows out to pasture more and giving them lower protein feed can also help to reduce harmful gasses.

But this new technology and these practices alone are unlikely to achieve the ambitious environmental goals.

‘I’m not a fire-starter’

The Farmer-Citizen Movement (BBB) is surging in the polls.

On a visit to a farm near the Dutch city of Deventer, party leader Caroline van der Plas expressed concern about the increasingly toxic nature of the debate.

She warned that small groups of frustrated farmers were being radicalised on social media, in Telegram groups and in chat rooms manipulated by far-right politicians who saw the potential to jump on the tractor protests to plough their own agendas.

“I understand their anger but I am not a fire-starter… and let’s be real, the country is not exploding, it’s not like there will be a civil war in the next months, but the government has to start talking to the farmers, not just talking but listening and really hearing them or things will get worse.”

Despite this, Ms Van der Plas says her party will not sit down with government negotiators: “We want the whole nitrogen policy and plans that are on the table right now put on hold and to look for other solutions.

“I said in the [parliamentary] debates, be careful what you wish for because when the farmers are gone, they are not going to come back. If we depend on imports – you see it with gas from Russia – we have a big problem.”

‘Broken system’

Natasja Oerlemans, head of food and agriculture at WWF Netherlands, believes farmers have the potential to be part of the solution.

In the Netherlands, farmers need to use nature as an ally, and that means having fewer cows and fewer pigs

-Natasja Oerlemans

Head of food and agriculture at WWF Netherlands

She says while some farmers might be forced to leave the industry, others could adapt and provide different services in a changing climate.

“Storing water when there’s too much rain – in a densely populated country like the Netherlands, this can provide huge opportunities for farmers to gain extra income and work in the future.”

But, Ms Oerlemans warns, the Netherlands is facing a painful period of uncertainly and unrest, describing the agricultural system as “broken”.

She says for years the government has failed to act on scientific data, meaning drastic measures are now needed to tackle the issue. The farming industry’s focus on increasing livestock productivity, she adds, has had a detrimental impact on the ecosystem.

“My lesson would be don’t follow the pathway that the Dutch agricultural system has followed over the past decades, because that’s a dead end.”