In a matter of days, Saudi Arabia carried out blockbuster agreements with the world’s two leading powers

WASHINGTON — In a matter of days, Saudi Arabia carried out blockbuster agreements with the world’s two leading powers — China and the United States.

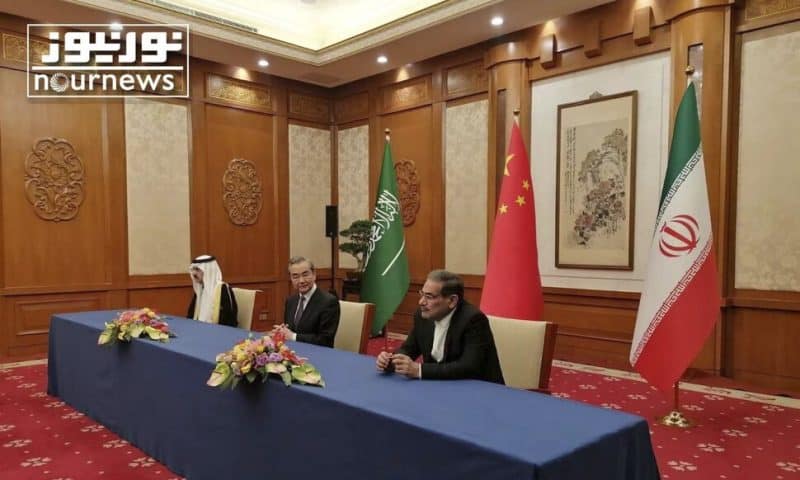

Riyadh signed a Chinese-facilitated deal aimed at restoring diplomatic ties with its arch-nemesis Iran and then announced a massive contract to buy commercial planes from U.S. manufacturer Boeing.

The two announcements spurred speculation that the Saudis were laying their marker as a dominant economic and geopolitical force with the flexibility to play Beijing and Washington off each other. They also cast China in an unfamiliar leading role in Middle Eastern politics. And they raised questions about whether the U.S.-Saudi relationship — frosty for much of the first two years of President Joe Biden’s term — has reached a détente.

But as the Biden administration takes stock of the moment, officials are pushing back against the notion that the developments amount to a shift in the dynamics of the U.S.-China competition in the Middle East.

The White House scoffs at the idea that the big aircraft deal signals a significant change in the status of the administration’s relations with Riyadh after Biden’s fierce criticism early in his presidency of the Saudis’ human rights record and of the Saudi-led OPEC+ oil cartel move to cut production last year.

“We’re looking forward here in trying to make sure that this strategic partnership really does in every possible way support our national security interests there in the region and around the world,” White House National Security Council spokesman John Kirby said of the U.S.-Saudi relationship. He spoke after Boeing announced this week the Saudis would purchase up to 121 aircraft.

But China’s involvement in facilitating a resumption of Iran-Saudi diplomatic ties and the major Boeing contract — one the White House said it advocated for — have added a new twist to Biden’s roller-coaster relationship with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

As a candidate for the White House, Biden vowed that Saudi rulers would pay a “price” under his watch for the 2018 killing of U.S.-based journalist Jamal Khashoggi, a critic of the kingdom’s leadership. More recently, after the OPEC+ oil cartel announced in October it was cutting production, Biden promised “consequences” for a move that the administration said was helping Russia.

Now, Washington and Riyadh seem intent on moving forward, and at a moment when China is at least dabbling in a more assertive Middle East diplomacy.

Saudi officials kept the U.S. up to date on the status of talks between Iran and Saudi Arabia on restarting diplomatic relations since they began nearly two years ago, according to the White House. Significant progress was made during several rounds of earlier talks hosted by Iraq and Oman, well before the deal was announced in China last week during the country’s ceremonial National People’s Congress.

Unlike China, the U.S. does not have diplomatic relations with Iran and was not a party to the talks.

The Iran-Saudi relationship has been historically fraught and shadowed by a sectarian divide and fierce competition in the region. Diplomatic relations were severed in 2016 after Saudi Arabia executed prominent Shiite cleric Nimr al-Nimr. Protesters in Tehran stormed the Saudi Embassy and Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, vowed “divine revenge” for al-Nimr’s execution.

White House national security adviser Jake Sullivan earlier this week said China was “rowing in the same direction” with its work at quelling tensions between the Gulf Arab nations that have been fighting proxy wars in Yemen, Syria, Lebanon and Iraq for years.

“This is something that we think is positive insofar as it promotes what the United States has been promoting in the region, which is de-escalation, a reduction in tensions,” Sullivan said.

But privately White House officials are skeptical about China’s ability, and desire, to play a role in resolving some of the region’s most difficult crises, including the long, disastrous proxy war in Yemen.

Iran-allied Houthis seized Yemen’s capital, Sanaa, in 2014 and forced the internationally recognized government into exile in Saudi Arabia. A Saudi-led coalition armed with U.S. weaponry and intelligence entered the war on the side of Yemen’s exiled government in 2015.

Years of inconclusive fighting created a humanitarian disaster and pushed the Arab world’s poorest nation to the brink of famine. Overall, the war has killed more than 150,000 people, including over 14,500 civilians, according to The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project.

A six-month cease-fire, the longest of the Yemen conflict, expired in October, but finding a permanent peace is among the administration’s highest priorities in the Middle East. U.S. special envoy to Yemen Tim Lenderking is visiting Saudi Arabia and Oman this week to try to build on the U.N.-mediated truce that has brought a measure of calm to Yemen in recent months, according to the State Department.

Beijing swooped in on the Iran-Saudi talks at a moment when the fruit was already “ripening on the vine,” according to one of six senior administration officials who spoke to The Associated Press on the condition of anonymity to discuss the private White House deliberations. The Iran-Saudi announcement coincided with Chinese leader Xi Jinping being awarded a third five-year term as the nation’s president.

The official added that if China can play a “reinforcing role” in ending hostilities in Yemen the administration would view that as a good thing. But both the White House and Saudi officials remain deeply skeptical of Iran’s intentions in the Yemen war or more broadly acting as a stabilizing force in the region.

“While these discussions were going on, in the last 90 days, we have interdicted five major weapons shipments coming from Iran to Yemen,” Gen. Erik Kurilla, commander of U.S. Central Command, told lawmakers on Thursday. “One of those shipments included components, inertial navigation systems for short-range ballistic missiles. So again, I think the implementation is a completely different matter.”

To date, China, which has a seat on the U.N. Security Council, has shown little interest in the Yemen conflict, Syria or the Israeli-Palestinian situation, according to administration officials. Yet, Xi this week called for China to play a bigger role in managing global affairs after Beijing scored a diplomatic coup with the Iran-Saudi agreement.

“It has injected a positive element into the peace, stability, solidarity and cooperation landscape of the region,” China’s Deputy U.N. Ambassador Geng Shuang told the U.N. Security Council on Wednesday. “We hope it can also create conducive conditions for improving the situation in Yemen.”

The administration officials said Beijing has shown modest interest in reviving the seven-party Iran nuclear agreement — of which it is a signatory — that President Donald Trump withdrew the U.S. from in 2018. The Biden administration put efforts to revive the nuclear agreement on hold last fall after protests broke out in Iran following the death in police custody of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini, who was detained for allegedly flouting Iran’s strict dress code for women.

To be certain, China — a major customer of both Iranian and Saudi oil — has been steadily increasing its regional political influence. Xi traveled to Riyadh in December and received Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi in Beijing last month.

But Miles Yu, director of the China Center at the Hudson Institute, said Xi’s call to be a more active player on the international stage would require Beijing to dramatically change its approach.

“China’s diplomatic initiatives have been based on one thing: money,” said Yu, who served as a China policy adviser to Secretary of State Mike Pompeo during the Trump administration. “They’ve made friends in Africa and Asia, but mostly it was monetary. These kind of transactional dealings do not forge permanent friendship.”

Not every move China takes to engage more deeply with the Middle East necessarily harms the United States, noted Sen. Chris Murphy, a Connecticut Democrat and a frequent critic of Saudi Arabia.

“But it’s probably true that China should pick up some of the cost of securing the oil that … frankly, is probably more important to them than to the United States in the long run,” Murphy said. “I think China has benefited by being a free rider on U.S. security investments in the region for a long time.”

The White House is not particularly concerned at the moment about the Saudis reorienting themselves toward China for several reasons, including that the Saudis’ entire defense system is based on American weapons and components, administration officials said. The officials added that it would take the Saudis at least a decade to transition from U.S. weapons systems to Russian or Chinese oriented systems.

Saudi Arabia’s reliance on U.S.-made weapons systems and the American military and commercial presence in the kingdom — some 70,000 Americans live there — have played a big part in the relationship weathering difficult moments over the years, said Les Janka, a former president of Raytheon Arabian Systems Co. who spent years living in the kingdom.

It would take “an unbelievable amount of activity to dismantle, given the reliance on American weapons, American technology, American training, everything that goes into it,” Janka said.