While NFT technology was created to give artists more control over their work, they have spawned a frenzy as collectors look to cash in.

On GivingTuesday, officials at New Jersey-based health care charity Sostento learned they would receive a donation of roughly $58,000 by the end of the week.

The donation was unlike any the nonprofit had received before. It was derived from the proceeds of the sale of a nonfungible token, or NFT, for a digital artwork called “The NFT Guild Philanthropist — Healthcare Heroes.”

You’ve likely heard of NFTs. They’re built on the same technology that underlies digital currencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum. These digital assets shot into the limelight in March 2021 after Mike Winkelman, known by his artist moniker Beeple, auctioned off an NFT for $69 million at Christie’s. Think of an NFT as a deed or token associated with a work of digital art, like an image, an audio recording, or a video. That token can be used to keep track of the file’s provenance and sale history, allowing someone to prove ownership of the asset.

While the technology was created to give artists more control over their work, NFTs have spawned a frenzy as collectors look to cash in. As that speculation intensifies, a growing number of charities have begun to explore fundraising efforts tied to NFTs. Although some NFT charity auctions have yielded eye-popping sums, others have had limited success. Complicating matters, NFTs use new technologies that are generating lots of questions for accountants and regulators.

The “Guild Philanthropist” NFT sold for 6.3 Ethereum, the equivalent of roughly $28,000. The artist provided a donation to match the sale price. For Sostento, accepting the donation was fairly simple. The organization worked with Giving Block, a nonprofit that helps other charities accept cryptocurrency, to convert the crypto into U.S. dollars. The NFT will also continue to benefit charities in the future. It was created with a provision that obliges proceeds of future sales to be given to charity.

But there is still a steep learning curve associated with NFTs and cryptocurrency, said Joe Agoada, CEO of Sostento, which develops software and communication products for the health care industry. Accountants advising Sostento cautioned against accepting NFTs and other cryptocurrency directly. Working with an intermediary to convert the NFT proceeds from ones and zeros to dollars and cents was crucial.

“It took a long time to understand how we could actually make this possible,” said Agoada.

Sostento wasn’t the only group to see a windfall from these novel tokens last week. Officials at Giving Block said they helped process roughly $1 million in charitable donations on GivingTuesday derived from the proceeds of NFT auctions. And on Dec. 7, Giving Block will launch the inaugural NFTuesday, a day focused on driving more NFT-derived philanthropy.

Some nonprofits have entered the NFT fray as a way to reach a broader audience.

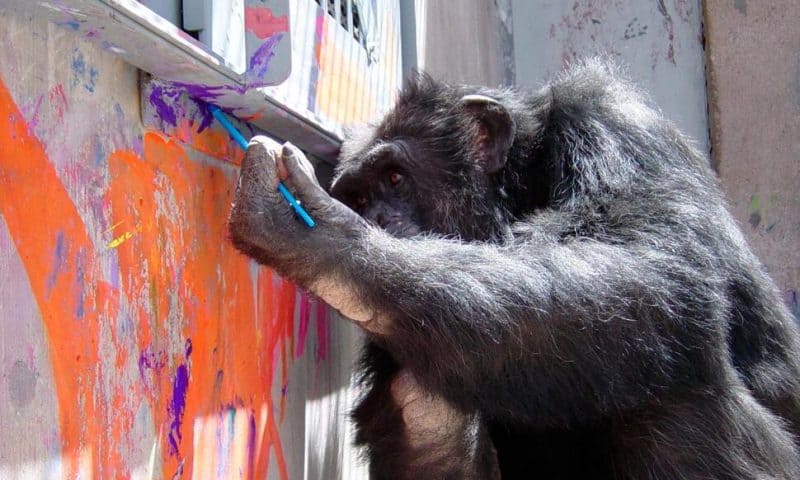

In July, officials at Save the Chimps, a chimpanzee refuge in Fort Pierce, Florida, scanned finger paintings done by three of its residents: Cheetah, Clay, and Tootie. From those scans, they created a series of NFTs and listed them for auction on Truesy, an NFT marketplace. Think of them like prints of a photograph. They were priced to sell at a value equivalent to about $25. Save the Chimps set up its NFT to provide a royalty to the charity in the event of future sales. The fundraising haul so far? Just a few hundred dollars.

“The exciting part was they were all first-time donors,” said Sara Halpert, the group’s marketing director.

That’s the appeal for many charities that have started to dabble in the world of NFTs and, more broadly, cryptocurrency. These collectors and investors could be a valuable new audience for fundraisers to tap, said Pat Duffy, CEO of Giving Block. They tend to be richer-than-average, financially savvy younger donors who are very active online.

“These are people a major-gifts officer should be connecting with and talking to,” said Duffy.

It’s less common for donors to give NFTs directly to nonprofits, but that’s happening, too.

Earlier this year, entrepreneur Eduardo Burillo donated an NFT titled “CryptoPunk 5293” to the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami. The work, which is part of a 10,000-piece series, depicts the pixelated avatar of a person sporting a short-bob haircut, pink lipstick, and a Mona-Lisa-like expression. As of Thanksgiving, the average sale price of a CryptoPunk was just under $500,000.

While NFTs may seem novel as an instrument of philanthropy, the assets tied to the tokens are similar to other forms of ephemeral art, such as performance art, video art, or art installations, said Alex Gartenfeld, artistic director at ICA Miami.

ICA Miami’s case is unique, at least so far. No other museums have yet accepted NFTs into their collections.

The biggest challenge for nonprofits — especially those that wish to hold an NFT as an asset — is that the existing accounting rules don’t really address NFTs, says Brian Mittendorf, a professor of accounting at Ohio State University who focuses on nonprofits. The NFT is technically different from the artwork itself, which raises heady questions about what is and is not being valued, or even what could be considered part of a museum’s collection.

“It captures both the challenges of charities dabbling in the cryptocurrency realm coupled with the challenges of charities seeking to raise funds off of things that are hard to value,” Mittendorf said. “There are just open questions from an accounting standpoint.”

Regulators, including the Securities and Exchange Commission, are beginning to examine how and when to treat NFTs as collectibles or securities. The eventual result of those decisions could have ramifications for charitable-accounting offices.

Charities are also experimenting with NFT-based fundraising in ways that go beyond the realm of digital art.

Environmental group Beneath the Waves, which focuses on ocean conservation, is auctioning off dozens of NFTs that each represent a real-life shark tag, with starting prices ranging from $500 to $20,000. The owners get the right to name their tagged shark and will receive updates on its movement through the oceans. One of the NFTs entitles the owner to take part in the group’s marine-research efforts in the Caribbean. Bidding closed at $23,000.

Rewilder.xyz, a new organization, is using NFT auctions to raise funds to buy land for reforesting efforts in the Amazon. For each donor who gives a minimum donation of 1 Ethereum, equivalent to approximately $4,400, the group will create an NFT entitling the owner to receive periodic updates about the land they have helped purchase. So far, the effort has raised nearly 60 Ethereum, equivalent to roughly $241,700 as of this writing.

“You basically buy a photo of the land,” said Robbie Heeger, CEO of Endaoment, a charity that sponsors donor-advised funds built on the Ethereum blockchain and helps other organizations accept crypto gifts. Endaoment helped Rewilder establish the campaign.

“It’s another way to basically involve your donor community in a sense of attachment and ownership over the work that’s happening at the nonprofit,” Heeger said.

Save the Chimps had environmental concerns about fundraising with NFTs. The computing process to maintain records of crypto transactions consumes a lot of energy. Those worries have led some organizations to reconsider accepting digital currencies as donations. Earlier this year, Greenpeace announced it would stop taking Bitcoin donations, for example.

Save the Chimps opted to list its NFTs on Truesy, which trades on Tezos, a digital-currency network that uses a less-energy-intensive process than Ethereum to perform the complex computing needed to prove ownership and provenance of a digital asset. In other words: These NFTs are greener than average.

The charity remains interested in the future of NFTs and their utility for philanthropy, said spokesperson Seth Adam. Whether that means featuring NFTs in its annual auction or collaborating with other artists, he said, “We are always looking at new NFT opportunities.”