With the debate over inflation dominating financial markets as the global economy reopens from the COVID-19 pandemic, investors are turning to a number of so-called alternative-data sources in an effort to get a more timely read on what’s happening to prices around the world.

While readings on the U.S. consumer-price index, producer-price index, and the Federal Reserve’s favorite measure — the personal consumption expenditure deflator — all come around once a month, they’re offering up a backward-looking picture of where prices stood around three to four weeks earlier.

“This is where real-time alternative data comes in,” said Yin Luo, senior analyst at Wolfe Research, in a phone interview, offering “a more timely measure of the price movements than the official data, which tends to be delayed.”

The ability to get a more timely read on market-sensitive data trends has been driving the widespread adoption of alternative data for years, but the COVID-19 pandemic may have supercharged interest as investors and economists scrambled to make sense of a largely unprecedented near-shutdown of economies and a subsequent, vaccine-enabled reopening that’s been plagued by supply-chain kinks and complicated by the spread of coronavirus variants.

Interest in macro-focused alternative data has likely quadrupled since the pandemic, said Luo.

Meanwhile, the so-called reflation trade — a bet that assets more sensitive to the economic cycle or otherwise poised to benefit from a surge in inflation would outperform their peers — has waxed and waned in 2021. Its path has depended on whether investors see inflation as in danger of soaring and possibly turning into a spiral or more likely to prove, in the Fed’s preferred term, transitory.

One of the more well-known resources comes from PriceStats, a business that grew out of a Massachusetts Institute of Technology initiative known as the Billion Prices Project in 2008. The project grew out of research conducted by economists Alberto Cavallo, now at Harvard, and Roberto Rigobon.

PriceStats, which joined with State Street in 2011 to bring its data to the financial services sector, scrapes the web, tracking daily changes in prices across a huge basket of goods in 23 economies. PriceStats focuses solely on “multichannel” retailers who offer products both online and offline, which cuts out big online-only retailers, including e-commerce juggernaut Amazon.com Inc. AMZN .

PriceStats scrapes product descriptions and prices, sorting them into classifications. It computes price changes each day and uses official weightings used in a particular country’s inflation gauge to create an index.

The result is a real-time look at a broad basket of goods for each country. Of course, not everything is online. And PriceStats, for example, doesn’t track used-car prices, which have skewed U.S. inflation data in recent months. It also doesn’t track house prices, for example, but offers proxies, such as building supplies, which have historically tracked those prices closely.

The data offers a look at inflationary pressures with a roughly two-day lag, as opposed to the lag of several weeks offered by official data, said Marvin Loh, senior global market strategist at State Street, in an interview. Equally important is having a price series for 21 different countries, he said, because inflation is a global topic, making it useful to see how global price pressures are manifesting themselves in individual countries and regions.

Loh said he’s found that online prices adjust more quickly than prices on the shelves. In 2020, when the pandemic hit, prices tracked by PriceStats fell much more quickly than was reflected by the official data. On the rebound, the basket was showing stabilization making its way into prices, while official data has reflected items not in the basket such as used cars and airline tickets.

The takeaway is that the data showed upward pressure relative to what a normal June or July would look like, “but not accelerating the way it did in early spring into summer.”

Investors can also attempt to discern expectations around inflation by tracking news stories. Ravenpack, an alternative-data provider that specializes in using natural language processing (NLP) to analyze news, said the approach yielded insights into a shift in investor expectations about inflation in May.

Ravenpack sets up systems for clients that track particular topics, with each news story being assigned a sentiment score, explained Inna Grinis, head of macro strategy at the company.

An article about rising inflation would receive a negative sentiment score, for example. The score also takes into account any magnitudes mentioned in the story, she explained. For example, if an article reported that inflation climbed 4%, the score would be larger than if prices were up by 1%.

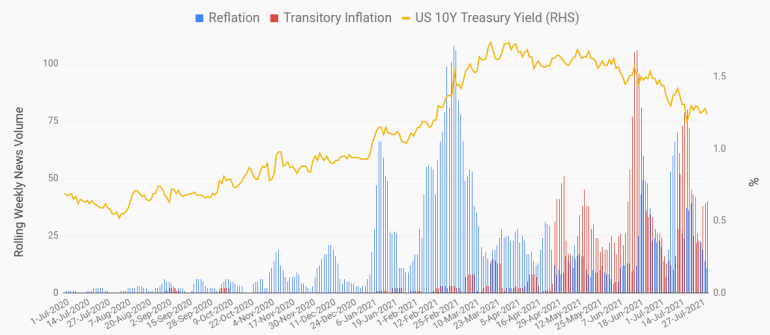

The data provided insights to clients perplexed by a pullback in U.S. Treasury yields after a spike earlier this year that had been attributed in part to expectations for a lasting resurgence in inflation. The chart below tracks the weekly counts of news articles containing the words “reflation” versus “transitory” and “inflation” in headlines.

Grinis said the approach allows users to track the importance of the “reflation” and “transitory inflation” narratives in market commentary in real time.

The chart shows the reflation narrative began gaining momentum in the summer of 2020, peaking in late February and early March, before the 10-year Treasury note yield TMUBMUSD10Y peaked out in late March just shy of 1.80%. On June 10, when the core consumer-price index came in at a stronger-than-expected 0.7% monthly rise, bond yields continued to decline, in line with the transitory inflation narrative, Grinis noted.

Since mid-June the reflation and transitory inflation narratives seem to be oscillating in importance, Grinis said. The reflation narrative rose around the release of June CPI data on July 13, which again came in much hotter than expected. The 10-year yield initially moved higher, but then fell back, in line with a fall in reflation concerns, she said.

The 10-year yield on Monday dipped below 1.15% to its lowest level in nearly six months. The U.S. stock market, meanwhile, has continued to climb over the course of 2021, but with different sectors and styles moving in and out of favor as expectations around inflation have shifted.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average DJIA is up more than 14% year to date, while the S&P 500 SPX has advanced more than 17% and the tech-heavy Nasdaq Composite COMP is up more than 14%.

NLP analysis can also be used by firms to monitor conference calls and corporate 10-Q and 10-K filings, which can give an aggregate view on rising input prices, plans to pass along price increases and other inflation markers, said Wolfe Research’s Luo.

While not as timely as data on spending or prices, such readings can offer insights on labor costs and labor shortages, such as rising pay at most big banks for junior bankers, Luo said. It also pays to scan central bank policy announcements, speeches and other documents to pick out patterns.

Of course, many alternative data sets are well out of the price range of individual investors. Moreover, no single data set should be viewed as a silver bullet that will give an investor the key to instant outperformance.

Using alternative data in addition to traditional data provides a more diverse set of inputs. As Luo has previously described, it echoes the investment-industry adage that describes holding a diversified basket of assets as the only “free lunch” in finance. The same principle applies to data.

But investors don’t necessarily have to break the bank to incorporate real-time data insights, said Nicholas Colas, co-founder of DataTrek Research.

“Our approach to data is to use freely available resources to evaluate market narratives,” he said in a July 23 note. “Because of the economic dislocations over the last 18 months, headline numbers — and the stories they seem to tell — are often misleading or just wrong.”

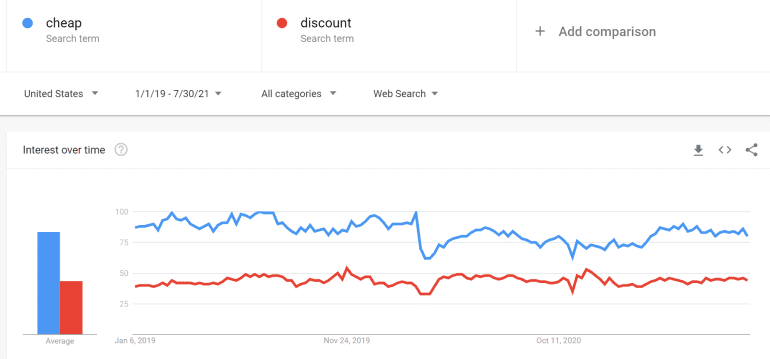

How the U.S. consumer responds to inflation is a key question for investors in the second half of this year, Colas said. DataTrek’s approach is to look at the volume of U.S.-based Google searches for terms like “cheap” and “discount.”

“An uptick would signal rising concerns about inflation that could lead to declining consumer demand,” he said. An updated chart (see below) showing search volumes since January 2019 shows that hasn’t started to happen. With volumes for both terms stable, stagflation doesn’t appear “even close to being an issue for the U.S. economy.”

The example, Colas said, shows that with “the wealth of no-cost information available now, it is possible to find the real story. You just have to know where to look.”