Majorities in multiple countries oppose the Olympic Games in Japan during a still-uncontrolled pandemic.

Despite the postponed 2020 Tokyo Olympics formally commencing on Friday July 23 with the Opening Ceremony, global opinions about this year’s games don’t reflect the usual fanfare surrounding the sporting event.

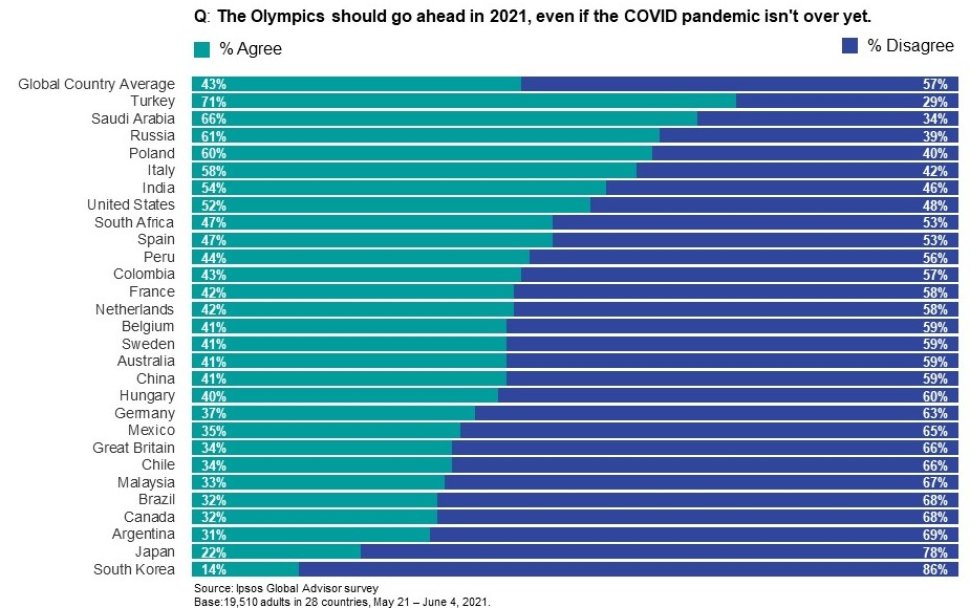

A recent poll by Ipsos Global Advisor, which surveyed 19,510 people across 28 countries between May 4, 2021 and June 4, 2021, reveals that 54% of respondents do not want the games to take place. In Japan, the percentage of respondents who oppose staging the 2020 Olympics grows to 78% – the second highest of any country surveyed, with respondents in South Korea being the most vehemently opposed to the games at 86%.

This year’s games undoubtedly differ from previous years – marking the first games to be hosted in an odd-numbered year, without live spectators and during a public health state of emergency in its host country. While the International Olympic Committee has put some provisions in place to ensure competing athletes are arriving in Tokyo safely – such as mandating quarantines for athletes who have come in close contact with an infected person and conducting frequent testing – Japan’s residents are still concerned about the consequences of the Olympics and Paralympics, which will bring together 15,000 athletes from over 200 countries.

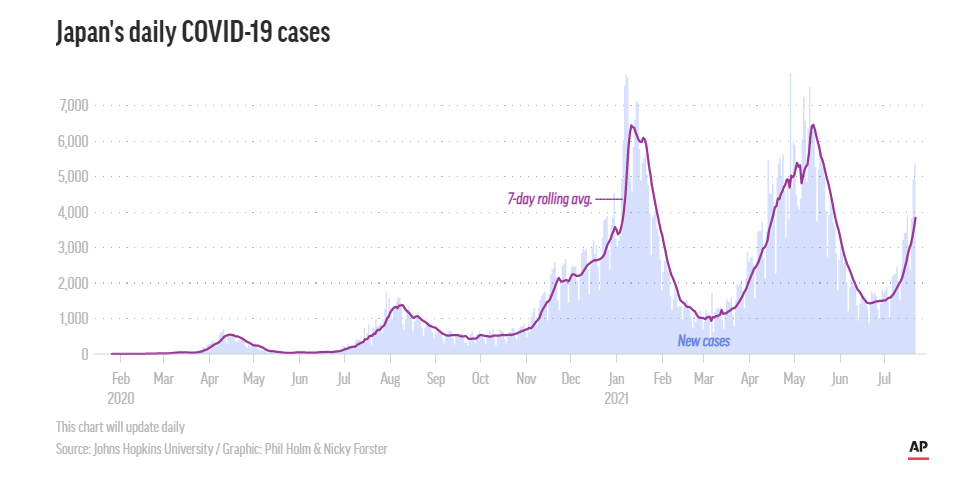

Those worries grew on Thursday, as Tokyo reported nearly 2,000 new cases of COVID-19, the highest daily figure in six months.

“We really haven’t seen anything like this in the political history of the Olympics, where you have all these people around the world saying it’s a bad idea to host the games,” Jules Boykoff, a former Olympic soccer player and researcher on sports politics, said during a panel discussion on the 2020 Tokyo Olympics and the future of the games.

For one, the games come at a particularly strenuous time in Japan’s battle against the COVID-19 pandemic. Currently, only 20% of the country is vaccinated and cases are still on the rise in the country. Along with protests from the Japanese public, many of Tokyo’s doctors have taken a stance against the games taking place.

The Tokyo Medical Practitioners Association, which represents about 6,000 primary care doctors, penned an open letter to Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga urging the games to be canceled in May. The letter cites Japan’s slow vaccine rollout and shortage of medical professionals and hospital beds as reasons against the Olympics. However, the power of canceling the Olympics solely resides with the IOC, not the host country, according to the contract between the organization and the city of Tokyo.[

“The through line with all of this and what much of what we’re witnessing in Tokyo in terms of the stress and strain that’s on the everyday people as well as the athletes is due to this through line of the International Olympic Committee, who is just acting in their own self-interest taking a gamble in this case with global public health,” Boykoff said. “Medical officials across the world and inside of Japan have long been clamoring for these Olympics to be canceled.”

Sponsors have also distanced themselves from the games because of the pandemic. Toyota, one of the top corporate sponsors for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics and a returning sponsor since 2015, has decided against running any Olympics-themed advertisements on TV in Japan.

Beyond concerns over the pandemic, Tokyo residents remain wary of hosting the Olympics because of the event’s impact on low-income communities. According to The Washington Post, about 300 people in Tokyo had been displaced for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics and relocated to three different neighborhoods by this time last year.

For some of these displaced residents, this is not their first time having their life uprooted by the Olympics. In 2019, Boykoff wrote an article for The Nation in which he interviewed two women who were displaced from their homes during the 1964 Tokyo Olympics only to be relocated for the same reason again in 2020.

“They were displaced twice by the Olympics, moved out of their community, and had it shattered for the Olympic spectacle,” Boykoff said during the webinar.[

Displacement is not new to the Olympics. For decades, poor communities in host countries have lost their homes and networks in favor of constructing the grandiose stadium required for the games. Seoul forcibly displaced 720,000 people for the 1988 games and Beijing moved 1.5 million people to make way for the stadium, pools and media centers required for the 2008 Games and as a part of a broader urban development project that rapidly unfolded in preparation for an international audience, according to the Center on Housing Rights and Evictions. The same happened leading up to the 2012 London Olympics, where a low-income housing development was demolished to make way for the event.

And then there is the unresolved question on whether hosting an international event on the scale of the Olympics is worth the cost for the host countries and its cities. The Greek experience of hosting the 2004 Olympics underscored the need for host countries to have a long-range plan for facilities specifically built or renovated for the games.

The 2016 Olympics were held in Brazil as the country was still wrestling with the Zika virus. Many Brazilians were priced out of seeing the Olympic events because of the cost of tickets. In the end, Brazilians were left with conflicted emotions over whether a renewed sense of pride was worth the estimated $12 billion cost of hosting the games.

Looking ahead, experts don’t know what the future of the games should look like, especially considering how costly it is for countries to host.

Yuhei Inoue, a researcher on sports management, said that the Olympics should focus more on bringing people together and satisfying local populations in its host country in order to improve the games for future years during the panel discussion.

“The Olympics simply is about making local people happier and making them feel like they can belong to the country,” he said. “Also, they can make connections with us all over again, they can feel like they are accepted living in a better society by hosting the Olympic Games. So I think focusing on the well-being, or happiness, of the local regions will satisfy the definition of that good Olympics.”