New York-based novelist Amitav Ghosh recently ordered a fountain pen from an artisanal maker in India.

“The last time I looked at his online list, it said my order would be ready in 95 weeks,” the Indian-born author, most recently, of Gun Island, told me.

Ghosh is willing to wait for his pen to arrive from the maker, located some 12,500km (7,767 miles) away, in the western city of Pune.

Here, Manoj Deshmukh, working with a small lathe machine in a small apartment, produces high quality handmade fountain pens that are sold all over the world. He has no employees. It takes anything between one to four days to make a single pen, sold under the brand name Fosfor, he says.

Six years ago Mr Deshmukh quit a thriving two-decade-long career as a software engineer and began making pens in his bedroom as a hobby.

One of his first pens was made of rose wood – he simply scraped some of it from a rolling pin in his kitchen, watched a few YouTube tutorials, made a wooden barrel on a tiny lathe machine and fitted it with an imported nib, feed section and converter. He put it up on online forums for pen collectors, and got $70 (£52) from an overseas customer.

Today, the waiting list for Mr Deshmukh’s pens stretches up to nearly two years. The 10 models come in a range of colours and cost between $70-$160 (£51-£118). “I am just passionate about making pens,” he says.

Fosfor is among a clutch of Indian artisanal pen makers who are attracting world-wide attention these days.

For years they have worked in relative obscurity, operating out of hole-in-the-wall workshops in cities and towns with a handful of employees. All of them are pen nerds, and some have quit thriving careers to make their hobby a business. Not so long ago, you had to visit their workshops to buy a pen. Then they began selling on ebay and Amazon. Now they book online orders on spiffy websites.

“India is a fast emerging source and market for artisanal pens. The world is also getting to know about us,” says MP Kandan, second-generation owner of the 50-year-old Ranga Pens, based in Tiruvallur in Tamil Nadu.

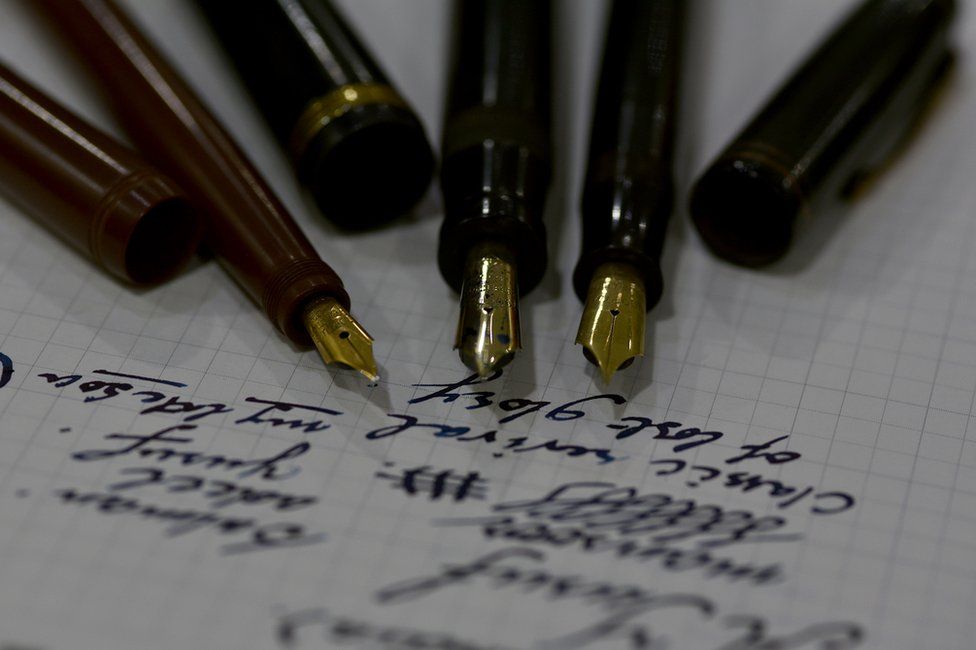

Indian artisanal pens are getting attention because of their pricing, design and looks. Most are made of ebonite, a warm and smoky hard rubber – which many modern pen makers do not use – and high quality acrylic, a shatter-resistant transparent plastic. Sleek pens are made out of titanium, brass, copper, steel, aluminium, wood – including fragrant sandalwood – and even buffalo horn. Many are hand painted in colourful local art. Nibs and ink filling systems are usually imported.

Doctors, lawyers, politicians and writers make up the bulk of customers. Most are men. There are avid collectors like Yusuf Mansoor, a retired geologist, who has a collection of more than 7,000 fountain pens in his house in the eastern city of Patna. “Great artisanal pens are conversation starters. They get attention when you carry it in your pocket. They are like men’s jewellery,” says Mr Mansoor.

India’s pen makers are a motley collection of family entrepreneurs, retirees, and people who have quit thriving professional careers to make money from their hobby. All of them are pen nerds. “Leaky nibs and stained shirts are a thing of the past. The number and variety of pens and sellers have grown,” Chawm Ganguly, a fountain pen buff who runs a popular blog on the subject, told me.

L Subramaniam, 48, who owns ASA Pens, in the southern city of Chennai, spent two decades in the telecoms industry before quitting in 2013 to start making artisanal pens. “As a kid, I used to roam around with 10 fountain pens in my pocket. So I had to make them one day. I crowd sourced designs on a WhatsApp group of customers and began producing,” he says. He makes up to 350 pens a month, costing between 1,000 [$14; £10.5] and 4,000 rupees each.

Three years ago Arun Singhi turned pen maker after four decades of work with a commercial pen firm. Today, his poky four-employee 200 sq ft pen workshop equipped with four lathe machines in a Mumbai suburb makes up to 200 pens of 50 models a month. Prices of his Lotus brand pens range from $40 to $475. Half are bought by foreign customers. Hand-painted pens are a big draw. “When I began I’d make 15-20 pens a month. Now I can’t keep up with the demand,” says Mr Singhi, 68.

Lakshmana Rao is a second generation maker from a family which has been making artisanal pens for 80 years out of a workshop near a river in the state of Andhra Pradesh. Their range of 300 models is eclectic with prices ranging from $5 to $680. Mr Rao says one of them pens, a $65 longish and heavy (46 gm) pen in milky white colour with a imposing cap and barrel which flares out into a majestic steel nib is very popular with clients. “People are fascinated by the pen because it is so big,” he says.

And Ranga Pens’ small workshop in a family home offers more than 400 models in 250 colours, and sells more than 500 pens every month. Most of its pens are sold abroad, and one of his more talked-about models is hand-crafted to resemble a “natural bamboo pattern”.

Pitchaya Sudbanthad, a New York-based author, who uses half a dozen homemade pens from India, says “each has its own feel”, and generally is “very reliable and made to hold a lot of ink”.

“When I get an artisanal Indian pen, I look for individual craft instead of factory engineering perfection, as I would with German and Japanese pen giants,” Mr Sudbanthad told me.

“They are generally pens from another age, similar to some Italian pen makers who still turn pens by hand, but without as much emphasis on precious materials and international branding.”

For a generation of avid users like Amitav Ghosh, getting the first fountain pen was a major rite of passage while growing up in India.

“The moment you graduated from a pencil or ballpoint, to a pen you knew you were no longer a child. The pen played a huge part in your life in those days. You’d have to carry a blotter, a rag to wipe your pen, and a dropper to fill it. And there were always ink stains on your clothes,” says Mr Ghosh, 64.

The joys of writing with pen never died. Mr Ghosh says he has a couple of pens that he’s really attached to.

“I have written literally millions of words with each of them.”