In the village of Dadivank, nestling in the Caucasus mountains, is an 800-year-old monastery. And parked outside is the Russian army.

The abbot, Armenian priest Father Hovhannes, greets the troops. “Thank you for being here,” he smiles.

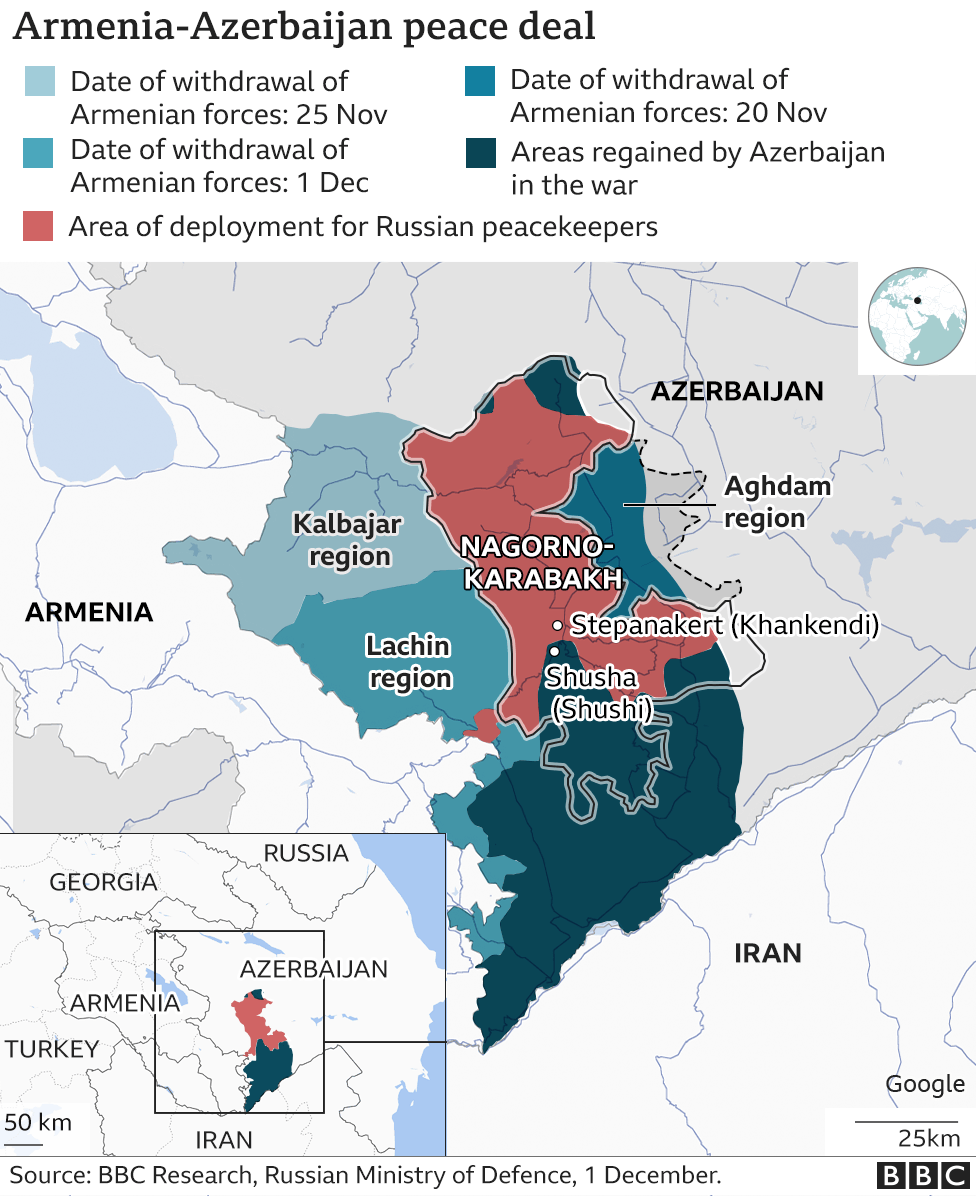

“We have orders to prevent this ancient place from being destroyed,” says a Russian soldier, one of 2,000 peacekeepers Moscow has deployed in and around the disputed territory of Nagorno-Karabakh.

“Traditionally it’s Russia that has guaranteed stability in this region,” the soldier tells me.

Dadivank is in Kalbajar district: one of several areas Armenia has now returned to Azerbaijan under the ceasefire agreement brokered by the Kremlin.

Moscow is hailing the deal as proof that Russia remains an influential force in the South Caucasus. But the recent six-week war has also revealed limits to Russia’s reach in its former empire.

‘Important foothold for Turkey’

Turkey has emerged as a rival player in Moscow’s back yard. It was Ankara’s military support that helped Azerbaijan defeat Russia’s traditional ally in the region, Armenia. Now Moscow has agreed to military observers from Turkey – a Nato country – being in the South Caucasus to monitor the ceasefire.

“What happened in Karabakh is truly a geo-political catastrophe for Moscow’s influence, not only in the South Caucasus, but across what remains of the post-Soviet space,” concludes political commentator Konstantin von Eggert.

“In effect we’ve seen an Armenian army, which was trained and armed by Russia, defeated by an Azerbaijani army trained and armed by the Turks. President Erdogan’s Turkey has gained a very important foothold in the region.”

“The conclusions that regional players like Turkey, China and Iran will draw from this will be that they can further muscle into the region, in Central Asia and in South Caucasus, without consulting too much with Moscow or fearing repercussions from the Kremlin.”

A 15-minute drive from Dadivank is Armenian-controlled Karabakh. There are Russian peacekeepers here, too. They’re protecting the ethnic Armenian population. But in the village of Getavan people are not excited to see them.

“We Armenians always thought that Putin was a good guy and on our side,” Araik tells me. “But in one stroke, with this deal, he’s given so much away to Azerbaijan. It’s so wrong.”

Not everyone shares that view. When I talked to some Armenian soldiers who were withdrawing from Karabakh, they said they were grateful to Russia for ending the fighting.

Russia facing challenges from neighbours

For Russia 2020 has been a year of geopolitical challenges across the former Soviet Union.

In Belarus – Russia’s closest ally – people power has been challenging a dictator who is being propped up by Moscow.

Despite signs that the Kremlin is growing impatient with Alexander Lukashenko, its decision to back him for now has aroused a degree of anti-Moscow sentiment rarely seen in Belarus.

In October a revolution in Kyrgyzstan caught Russia off guard.

And last month the Kremlin backed the loser in Moldova’s presidential election. Pro-Western politician Maia Sandu defeated the pro-Moscow incumbent Igor Dodon.

Still, the example of Moldova shows that, despite setbacks, Russia still has ways of exerting influence over some of its neighbours.

Russia has troops in Moldova. Or rather, a part of the country that has broken away and declared itself independent: Trans-Dniester.

The Russian soldiers are officially there as peacekeepers. But they give the Kremlin political leverage should the Moldovan leadership attempt to pivot away from Moscow’s sphere of influence.

“Our objective is to get closer to the EU and hopefully, one day, to become a member of the European Union,” President-elect Sandu tells me when we meet in the capital Chisinau.

“But would Russia let that happen?” I ask her. “Would Russia let Moldova join the EU?”

“It’s our choice. In the end it’s the sovereign decision of our country what model of development it wants to choose.”

“But Russia has 1,500 troops in your country,” I say.

“True, but we have been demanding and will continue to demand the withdrawal of the troops.”

‘Let these countries go’

Is there a real benefit to Russia maintaining a zone of influence in its neighbourhood?

“If you did the calculation, how many resources Russia is investing in keeping this periphery in its sphere of influence, and how much Russia would gain from economic returns, trade, security, investment and lack of trouble with its major markets in Europe, I think the equation would say let these countries [in the periphery] go,” says Alexander Gabuev, a senior fellow at the Moscow Carnegie Centre.

“But for the Kremlin it has an emotional attachment. And the Kremlin’s situation room is dominated by people from a counter-intelligence background who see threats all over, a Western spy under every tree. So they look at these countries as a security belt.”

Ultimately, though, Russia’s room for influencing the old Soviet space may be limited by new realities: an increasing number of regional players, including China, Turkey, America and the EU. And by Moscow’s current status as an ex-empire.

“A significant part of Russian society is still wedded to the idea of having a sort of empire,” believes Konstantin von Eggert. “But it will have to say goodbye to it quite soon. Historically speaking. Russia itself is undergoing a transition from an empire to a nation state and this is an inevitable process.”