Stubble burning in northern India has long been a major cause of air pollution, but efforts to stop it fail every year. The BBC’s Krutika Pathi and Arvind Chhabra find out why.

Plumes of smoke from Avtar Singh’s paddy fields envelop his village in Punjab state’s Patiala district. Mr Singh has just finished burning left-over straw – known as stubble – to clear the soil for the next crop.

The smoke is likely to travel as far as Delhi, some 250km (155 miles) away, adding to the national capital’s toxic haze. It’s not just Delhi that suffers. Stubble burning has created a massive public health crisis – its fumes pollute swathes of northern India and endanger the health of hundreds of millions of people.

And it’s more dangerous this year with Covid-19 ravaging the country as pollution makes people more vulnerable to infection and slows their recovery. According to some estimates, farmers in northern India burn about 23 million tonnes of paddy stubble every year.

Governments have tried to stop the practice. They’ve pitched alternatives, they’ve banned it, they’ve fined farmers for continuing to do it and they’ve even thrown a few of them in jail.

They’ve also tried to reward good behaviour – in 2019, the Supreme Court ordered a clutch of northern states to give 2,400 rupees ($32; £24) per acre to every farmer who didn’t burn stubble.

Mr Singh, who didn’t do it last year, was hoping to get this reward. “We waited a whole year, but we got nothing,” he says. “So, like many others, I decided to burn the stubble this year.”

In August, the Punjab government admitted they couldn’t afford to pay so many farmers. “I don’t know any farmer who has been paid this,” says Charandeep Grewal, a farmer.

As pollution levels grow, so has the chasm between the country’s farmers and policy-makers, who are trying to fix a broken system that has incentivised bulk production over the decades.

Experts say it’s partly due to policies that encourage farmers to grow more and not less. A spate of farmer-friendly decisions and cheap subsidies in the 1960s turned Punjab and Haryana into India’s biggest contributors of food grains.

But unlike then, India’s granaries are no longer empty and the system, which has changed little, is now at loggerheads with strained efforts to clean up the air.

The solutions that haven’t stuck

What complicates matters is that farmers are a crucial vote bank. That’s why court orders like bans and heavy fines often remain unenforced. “The politicians who need to enforce it would have to risk the ire of thousands of farmers – which they won’t do,” says agricultural economist Avinash Kishore.

Meanwhile, farmers continue to avail free electricity and heavy subsidies on paddy fertiliser.

“The behaviour of farmers depends on the policies you put into place. Things like free electricity and cheap fertilisers are causing havoc,” says agricultural economist Ashok Gulati.

But farmers say they get the lion’s share of the blame, although their stubble is only one of many sources of Delhi’s air pollution. Others include dust, industrial and vehicular emissions, and incineration.

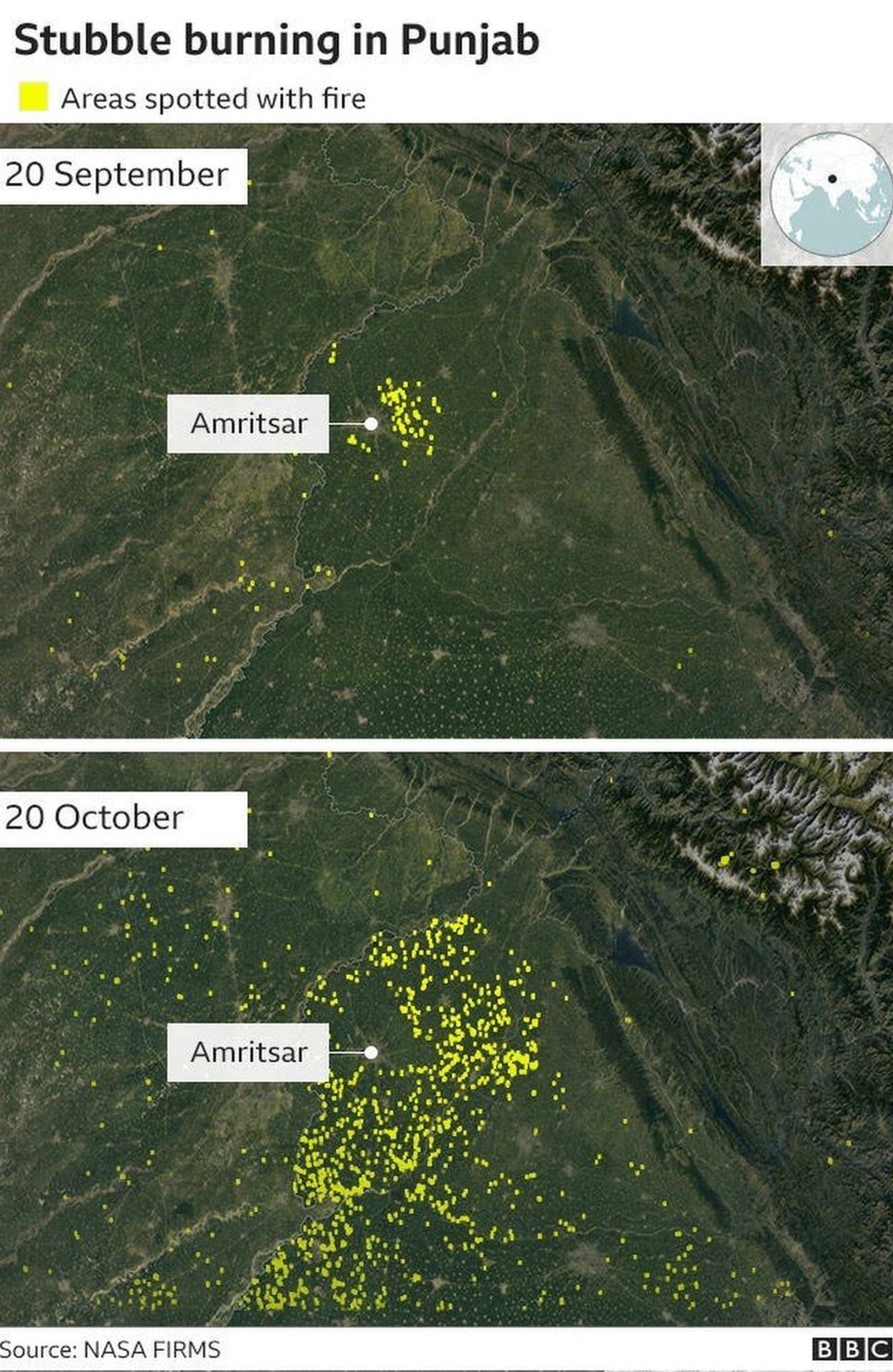

Weather plays a role too. Farmers burn stubble twice a year – in summer and at the onset of winter. The first time they do it, the warm breeze disperses it quickly. But the second time, in September or October, plummeting temperatures and low wind speed spread the smoke far and wide.

“The share of stubble burning in Delhi’s pollution can range from 1% to 42%, depending on wind speed and direction,” says Dr Gulati.

But a new environment ministry report says the average contribution has grown from 10% in 2019 to 15% this year.

The government has tried offering alternative technology, but that comes with its own share of problems.

For instance, take the Happy Seeder – a machine mounted on a tractor which removes the paddy straw while simultaneously sowing wheat for the next harvest. It was touted as eco-friendly, fast and effective. The government picked up 50 to 80% of the bill, depending on whether it was an individual farmer or a group.

Inderjit Singh, a wealthy farmer in Punjab, says he didn’t burn any stubble this harvest because he got a Happy Seeder last year.

But it doesn’t come cheap – the machine needs a tractor to work and the two combined can cost up to $15,000 (£11,229). “This explains why many farmers burn stubble – they can’t afford not to,” Mr Singh adds. And even for those who can, getting their hands on the machine has proved difficult due to long wait times and dwindling stock.

Another potential game-changer, a bio-decomposer developed by the Indian Agricultural Research Institute, turns crop residue into manure in 15 to 20 days. But some farmers say they don’t have so much time between crops.

“We aren’t allowed to plant paddy in the summer since the crop requires a lot of water and the logic is to conserve water during the heat,” says Mr Grewal. “If we were allowed to sow earlier, we would have more time between crops to get rid of the residue.”

Does India need another farming revolution?

But some experts, like Dr Gulati, say all these efforts are “irrelevant” to a degree.

Instead, he suggests tackling it at the root – subsidise crops other than paddy, the source of most stubble burning. “Policy and money should incentivise farmers in the region to plant more fruits and vegetables,” he says. “India needs more vitamins and protein rather than wheat and rice.” This, he adds, will create more greenery and since vegetable and fruit crops don’t leave stubble, it’ll bring down the number of open fires.

But to move forward, India may need to start from the beginning. Or at least 1966, when Punjab, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh were chosen to lead the country’s Green Revolution, which turbo-charged crop production by adopting modern technology and high-yielding varieties of seeds.

“Growing so much paddy in northern India was always going to cause issues – its topography isn’t suited for the crop,” says Dr Gulati. Paddy is incredibly water-hungry, making it easier to grow in regions with high groundwater, which Punjab doesn’t have.

More than 50 years on, experts say such intensive farming has not only led to air pollution, but is likely to spark other devastating consequences. “Water tables in these states are depleting rapidly – future generations are staring at a water crisis,” Dr Gulati adds.

Farmers realise this is unsustainable but say they don’t have a choice because the government is not offering them effective solutions.

“The way we farm has deeply affected the health of millions across states, but the effects are felt first-hand by the farmer before they reach the people of Delhi,” says Mr Grewal.

“We’re literally in the eye of the smoke, but nobody is concerned about that.”