Indonesian officials are vowing to end the controversial custom of bride kidnapping on the remote island of Sumba, after videos of women being abducted sparked a national debate about the practice.

Citra* thought it was just a work meeting. Two men, claiming to be local officials, said they wanted to go over budgets for a project she was running at a local aid agency.

The then 28-year-old was slightly nervous about going alone but keen to distinguish herself at work, so she pushed such concerns aside.

An hour in, the men suggested the meeting continue at a different location and invited her to ride in their car. Insisting on taking her own motorbike she went to slide her key into the ignition, when suddenly another group of men grabbed her.

“I was kicking and screaming, as they pushed me into the car. I was helpless. Inside two people held me down,” she says. “I knew what was happening.”

She was being captured in order to be wed.

Bride kidnapping, or kawin tangkap, is a controversial practice in Sumba with disputed origins which sees women taken by force by family members or friends of men who want to marry them.

Despite long-standing calls for it to be banned by women’s rights groups, it continues to be carried out in certain parts of Sumba, a remote Indonesian island east of Bali.

But after two bride kidnappings were captured on video and widely shared on social media, the central government is now calling for it to end.

‘It felt like I was dying’

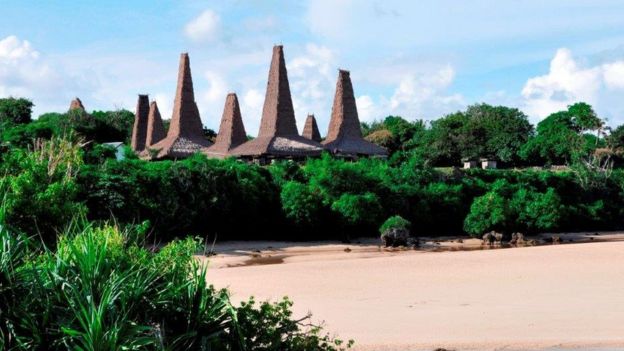

Inside the car, Citra managed to message her boyfriend and parents before arriving at a traditional house, with its high peaked roof and solid wooden pillars. The family who kidnapped her, she then realised, were distant relatives from her father’s side.

“There were lots of people waiting there. They sounded a gong as I arrived and started doing rituals.”

An ancient animist religion, known as Marapu, is widely practised in Sumba alongside Christianity and Islam. To keep the world in balance, spirits are appeased by ceremonies and sacrifices.

“In Sumba, people believe that when water touches your forehead you cannot leave the house,” Citra said. “I was very aware of what was happening, so when they tried to do that I turned at the last minute so that the water didn’t touch my forehead.”

Her captors told her repeatedly that they were acting out of love for her and tried to woo her into accepting the marriage.

“I cried until my throat was dry. I threw myself on the ground. I kept jabbing the motorbike key that I was holding into my stomach until it bruised. I hit my head against the large wooden pillars. I wanted them to understand I didn’t want this. I hoped they would feel sorry for me.”

For the next six days she was kept, effectively a prisoner in their house, sleeping in the living room.

“I cried all night, and I didn’t sleep. It felt like I was dying.”

Citra refused to eat or drink anything the family offered her believing it would put her under a spell: “If we take their food, we would say yes to the marriage.”

Her sister smuggled food and water to her while her family, with the support of women’s rights groups, negotiated her release with village elders and the family of the potential groom.

No position to negotiate

Women’s rights group Peruati has documented seven such bride kidnappings in the last four years, and believe many more have taken place in remote areas of the island.

Just three women, including Citra, ended up being freed. In the two most recent cases that were captured on video in June, one woman stayed in the marriage.

“They stayed because they didn’t have a choice,” says activist Aprissa Taranau, the local head of Peruati. “Kawin tangkap can sometimes be a form of arranged marriage and women are not in a position to negotiate.”

She says those that do manage to leave are often stigmatised by their community.

“They’re labelled as a disgrace and people say they will not be able to get married now or have children. So women stay because of a fear of that,” she says.

That is what Citra was told.

“Thank God I am now married to my boyfriend and we have a one-year old child,” she says with a smile, three years on from her ordeal.

Promises to outlaw the practice

Local historian and elder Frans Wora Hebi argues the practice is not part of Sumba’s rich cultural traditions and says it is used by people wanting to force women to marry them without consequences.

A lack of firm action by custodial leaders and the authorities means the practice continues, he says.

“There are no laws against it, only sometimes there is social reprimand against those who practice it but there is no legal or cultural deterrent.”

Following a national outcry, regional leaders in Sumba signed a joint declaration rejecting the practice early this month.

Women’s Empowerment Minister Bintang Puspayoga flew to the island from the capital, Jakarta, to attend.

Speaking to the media after the event she said: “We have heard from custodial leaders and religious leaders, that the practice of capture and wed that went viral is not truly part of Sumba’s traditions.”

She promised that the declaration was the beginning of a wider government effort to end the practice that she described as violence against women.

Rights groups have welcomed the move but described it as “a first step in a long journey”.

Citra says she is grateful that the government is now paying attention to the practice and hopes, as a result, no one will have to go through what she did.

“For some this may be a tradition from our ancestors. But it’s an out of date custom that must stop because it’s very damaging to women.”