Ethically minded entrepreneurs are turning back the clock to sweep the scourge of bunker fuel from the oceans

They fan out across the seas like a giant maritime dance, a ballet of tens of thousands of vessels delivering the physical stuff that has become indispensable to our way of life: commodities and cars, white goods and gas and grains, timber and technology.

But shipping – a vast industry that moves trillions of pounds-worth of goods each year – is facing an environmental reckoning. Ships burn the dirtiest oil, known as bunker fuel; a waste product from the refinery process, literally scraping the bottom of the barrel, the crud in crude. It’s so thick that you could walk on it at room temperature.

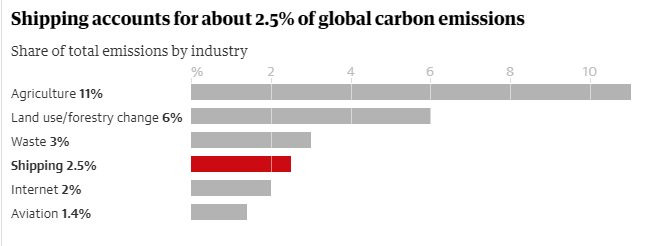

As a result, shipping is a major polluter – responsible for about 2.5% of global carbon emissions. Not surprisingly, innovators are starting to wonder if there is another way.

“Around 90% of everything we consume [in Britain] spends some time at sea, so we urgently need to make the transportation of goods more sustainable,” says Will Templeman, an environmental scientist-turned-entrepreneur.

Templeman’s eureka moment came during a visit to the supermarket when he was agonising over the food miles in his trolley. He wondered if it would be possible to transport things such as coffee and chocolate with zero emissions. Then he remembered that this was how goods used to travel. By sailing ship.

A quick online search revealed that a Dutch company was doing exactly that.

The owners of Fairtransport were inspired to revive sail cargo after witnessing at first hand the yellow smog caused by commercial vessels. They restored two ships, a 70-year-old minesweeper renamed the Tres Hombres and a wooden ketch called Nordlys that dates back to 1873.

Templeman arranged to board the Tres Hombres, sailing from the Azores to the Netherlands. “I was watching the ocean and it came like a ghost ship through the dawn mist. It looked like a pirate vessel. I was so excited.”

He dreamed of launching his own ship but realised that the first step was to make full use of the sailing vessels already in service.

He set up as a broker and together with his business partner, Will Adeney, went in pursuit of products to sell. They found their perfect olive oil in Portugal and arranged to have it shipped to Devon on board the Nordlys. They later sourced coffee beans in Colombia, and shipped them to Europe on the Tres Hombres. Their business, Shipped by Sail, was born.

It joined a growing network of brokers and sailors passionate about transporting goods by wind power. The next step: to boost demand for this kind of transportation.

“Consumers already understand organic produce and fair trade, and the next step is clean transport,” says Cornelius Bockermann, who founded Timbercoast, a German sail cargo company that has restored a schooner from 1920, and is now refitting a second.

Clean transport is the missing link, as many so-called sustainable or ethical goods are currently carried on ships that pollute the air and sea. The perfect example of this is plant-based meat, shipped around the world from California.

British couple Marcus and Freya Pomeroy-Rowden built their ship, the Grayhound, as a replica of an 18th-century lugger, and carry cargo between the UK and France, bringing West Country ale to Brittany and French wine to Cornwall. They supply small businesses along the way, for example providing wines to Dibble & Grub on the Isles of Scilly. The couple enjoy the lifestyle of spending months at sea, making a living, while making a difference.

Advertisement

Marcus says they’re bringing trade back to a human scale. “We’re taking quality products and transporting them direct to a distributor. We can understand and explain the whole chain for our products, from manufacture to the table.”

In France, TransOceanic Wind Transport has developed a labelling system with a voyage number, allowing the customer to see how products reached them.

Broker Alex Geldenhuys launched New Dawn Traders in the UK about six years ago and is still developing her “voyage co-op” model, bringing together farmers, ships and buyers.

Geldenhuys has been inspired by local food communities and vegetable box schemes and wants to extend that movement overseas, building relationships with distant farmers to bring ethically produced, high-quality produce to the UK with a carbon footprint that is close to zero. She is seeking “port allies” to promote the idea in coastal communities, encouraging customers to pre-order products from the ships and turning collection events at the docks into celebrations of the whole process.

A few weeks ago a French schooner, De Gallant, sailed into Bristol laden with produce from Portugal; the first time a tall ship had brought cargo to the city for decades. It was an emotional moment for Geldenhuys and the climax of years of work.“It was beautiful to watch her sailing in under the suspension bridge,” she says. Local people milled around the ship, sampling olive oil, almonds and wines.

Geldenhuys acknowledges that currently she can only deliver to her customers twice a year. Templeman says: “Restaurants and other businesses need a regular supply to be reliable. So we’re warehousing goods.” Olive oil on De Gallant was transported by electric van to a restaurant in Bristol.

The biggest challenge for sail cargo is scale. There are currently only a few small ships operating. Most companies feel that the time is ripe for expansion and have plans to build larger vessels. One of the founders of Fairtransport, Jorne Langelaan, has set up a new venture called EcoClipper to facilitate emission-free shipping worldwide. He is planning for more sailing ships running more routes more frequently.

In Costa Rica, Canadian Danielle Doggett is building a sailing ship called Ceiba, which looks set to become the largest in the world. The project uses tropical trees that have fallen in storms, and more trees are planted as the building proceeds.

Ceiba will be able to carry 250 tonnes of cargo (Tres Hombres and De Gallant take 35 tonnes), which is equivalent to around 10 containers. Yet this is still much smaller than the historic tea clippers, such as the Cutty Sark, and dwarfed by the largest modern container ships, which can carry more than 20,000.

The shipping industry knows that change is on the horizon. From next year new regulations will further limit sulphur oxide emissions from ships. The International Maritime Organization has announced its ambition to halve greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. The world’s largest shipping company, Maersk, has gone further, pledging to be carbon-neutral by 2050.