The US is sending a Patriot missile-defence system to the Middle East amid escalating tensions with Iran.

A warship, USS Arlington, with amphibious vehicles and aircraft on board, will also join the USS Abraham Lincoln strike group in the Gulf.

And US B-52 bombers have arrived at a base in Qatar, the Pentagon said.

The US said the moves were a response to a possible threat to US forces in the region by Iran, without specifying. Iran dismissed the claim as nonsense.

Tehran has described the deployments as “psychological warfare” aimed at intimidating the country.

Iran has also suggested it may resume uranium enrichment nuclear activities.

Why is the US sending additional forces?

The Pentagon says US forces are responding to a possible threat to US forces, but did not offer any specifics regarding those threats.

The latest Pentagon statement on Friday said only that Washington was “ready to defend US forces and interests in the region”, adding that the US did not seek conflict with Iran.

There are about 5,200 US troops currently deployed in neighbouring Iraq.

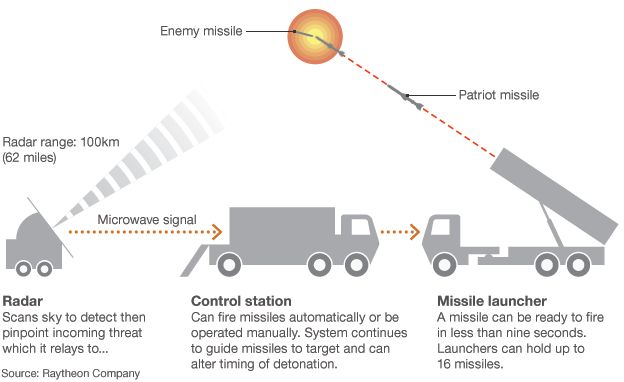

The Patriot system can counter ballistic missiles, cruise missiles and advanced aircraft.

Officials told US media the USS Arlington had already been scheduled to go to the region, but its deployment was brought forward to provide enhanced command and control capabilities.

The USS Abraham Lincoln passed through the Suez Canal on Thursday, US Central Command said.

Iran’s semi-official Isna news agency quoted a senior Iranian cleric, Yousef Tabatabai-Nejad, as saying that the US military fleet could be “destroyed with one missile”.

What’s the state of US-Iran relations?

Last year, US President Donald Trump unilaterally withdrew from a landmark nuclear deal America and other nations had agreed with Iran in 2015.

Under the accord, Iran had agreed to limit its sensitive nuclear activities and allow in international inspectors in return for sanctions relief.

Last month, the US also blacklisted Iran’s elite Revolutionary Guard Corps, designating it as a foreign terrorist group.

The White House proceeded to end exemptions from sanctions for five countries – China, India, Japan, South Korea and Turkey – that were still buying Iranian oil.

The sanctions have led to a sharp downturn in Iran’s economy, pushing the value of its currency to record lows, driving away foreign investors, and triggering protests.

The Trump administration hopes to compel Iran to negotiate a “new deal” that would cover not only its nuclear activities, but also its ballistic missile programme and what officials call its “malign behaviour” across the Middle East.

Iran has repeatedly threatened to retaliate to the US measures by blocking the Strait of Hormuz – through which about a fifth of all oil consumed globally pass.

Earlier this week Iran announced that it had suspended two commitments under the 2015 accord in response to the economic sanctions the US had re-imposed.

It also threatened to step up uranium enrichment if it was not shielded from the sanctions’ effects within 60 days.

European powers said they remained committed to the Iran nuclear deal but that they “reject any ultimatums” from Tehran to prevent its collapse.

Pressure or more?

The real battle for the fate of the Iran nuclear deal has begun.

In the year since the Trump administration unilaterally withdrew from the deal, Iran and all the other parties have carried on regardless. And the International Atomic Energy Agency, the global nuclear watchdog, has repeatedly given Tehran a clean bill of health. Iran has been living up to its part of the bargain.

But Iranian compliance was not the issue for the Trump administration, which says simply that this is a bad deal. The US’s main European allies, along with Russia and China, disagree. So the Trump administration has been ratcheting up the pressure on Tehran.

The pressure on Iran’s economy has been severe and the Iranian government has now decided to act – saying it will no longer respect restrictions on storing enriched uranium and heavy water, and setting deadlines for the other parties to implement their commitments.

A difficult couple of months of diplomacy lie ahead, with no guarantee of success. The Trump administration must see its ultimate goal – the collapse of the nuclear deal – as now being in sight. But the danger of conflict – albeit by accident rather than design – is growing.