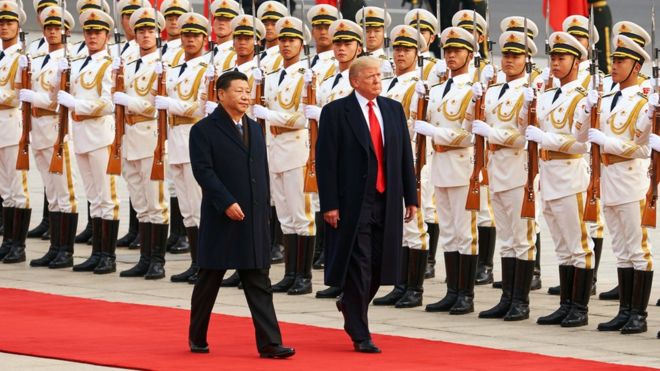

A US-China trade deal – if it happens – is unlikely to end the rivalry between the two economic giants.

Both sides have fought a trade war over the past year with damaging consequences for the global economy.

But many say their dispute goes well beyond trade – it represents a power-struggle between two very different world views.

Deal or no deal, that rivalry is only expected to broaden and become more difficult to resolve.

“We have entered into a new normal in which US-China geopolitical competition has intensified and become more explicit,” says Michael Hirson, Asia director at consultancy firm Eurasia Group.

“The trade deal will moderate one phase of the US-China power struggle, but only temporarily and with limited effect.”

The US-China rivalry is likely to play out next in the crucial technology sector, analysts say, as both sides try to establish themselves as the world’s technology leader.

Issues around technology transfer have been key during trade talks between the world’s two largest economies in recent months.

“Every country now correctly recognises that their prosperity, their wealth, their economic security, their military security is going to be linked to keeping a technological edge,” says Stephen Olson, research fellow at global trade advisory body Hinrich Foundation.

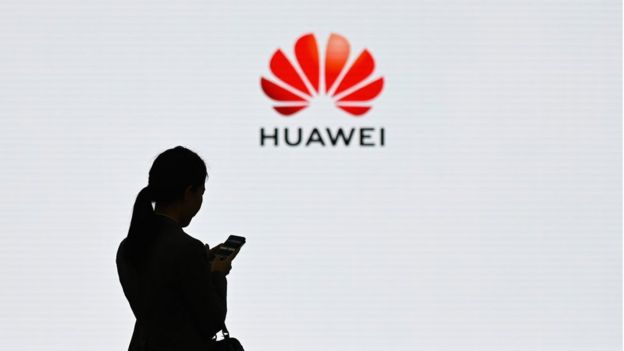

The technology battle

Many say the US-China technology battle is already under way – and China’s tech giant Huawei is at its very centre.

Huawei has been the focus of intense international scrutiny lately, with the US and other countries raising security concerns about its products.

The US has restricted federal agencies from using Huawei products and has encouraged allies to shun them.

Australia and New Zealand have both blocked the use of Huawei gear in next-generation 5G mobile networks.

But Huawei has said it is independent from the Chinese government. Its founder Ren Zhengfei told the BBC in February that his company would never undertake any spying activities.

The dispute reached fever pitch with the arrest of the founder’s daughter in December, and more recently Huawei’s lawsuit against the US government.

Huawei has also gone on a public relations offensive, placing a full-page ad in the Wall Street Journal telling Americans not to “believe everything you hear”.

“The term ‘cold war’ is overused in the context of overall US-China tensions, but is increasingly accurate in describing their technology competition,” says Mr Hirson.

The dispute over Huawei is “symptomatic of this intensified geopolitical competition,” he adds.

“This rivalry is far more difficult to resolve than pure trade issues.”

How did we get here?

US concerns about China have grown in recent years, along with China’s influence around the world.

Its massive Belt and Road Initiative, the Made in China 2025 plans, and the growing importance of companies like Huawei and Alibaba have all contributed to those fears.

US Vice President Mike Pence summed up the mood in a speech in October, saying China had chosen “economic aggression”, rather than “greater partnership” as it opened its economy.

Hopes China would embrace a more Western model has given way to a recognition that China’s economy has boomed alongside a state-run system, not in spite of it.

“China has become much more explicit in its ambitions in the last few years,” says Andrew Gilholm, director of analysis for China, at consultancy Control Risks.

“Therefore nobody is imagining that China is going to follow a Western liberal democratic model, or converge towards a market economy in the way that people hoped a few years ago.”

Some analysts think a stand-off between the two sides was inevitable.

Their different systems have always made them awkward bedfellows in the global economy, while clashes between existing and rising powers are common in history.

“What we are dealing with here is friction between traditional free market economics, free trade economics, Washington consensus principles versus – for the first time – a huge, technologically sophisticated, centrally-managed economy that is playing the game by a different set of rules,” says Mr Olson.

What happens now?

As the technology race gathers pace, analysts expect the US to continue to use non-tariff measures to push back against China.

Restrictions on Chinese investment into the US, limits on the ability of US firms to export technology to China, and further pressure on Chinese companies are all tools that could be used, they say.

“Non-tariff measures don’t get the attention from markets that tariffs do, partly because their impact is harder to quantify, but they can have far-reaching impact,” says Mr Hirson.

A new US law passed last year could facilitate this push-back.

It strengthened the government’s power to review – and potentially block – business deals involving foreign firms by expanding the type of deals that can be reviewed by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the US (CFIUS).

The committee vets foreign investments to see if they pose a risk to national security.

Last year, even before the new law passed, a high-profile deal involving the sale of US-based money transfer firm MoneyGram to Alibaba’s digital payments arm Ant Financial collapsed when the companies did not get the required approval from CFIUS.

New US-China norm?

How US-China relations develop from here will partly depend on the kind of trade deal they strike.

Burdened by tit-for-tat tariffs, both sides have shown a willingness to talk since agreeing on a truce in December.

But analysts say the relationship between the two giants could look different going forward irrespective of any trade deal.

They could have “an entirely cooperative, flourishing, mutually beneficial relationship” in certain areas but put up barriers in others in what Mr Olson described as a “selective decoupling”.

An increasing number of areas could be fenced off, particularly those related to technology, he says.

“Is Huawei ever going to, in a significant way, be able to participate in the construction of the 5G network in the United States? It seems unlikely.”