French President Emmanuel Macron has described Africa as “the continent of the future”, but it may also save his country’s language from the decline it is experiencing elsewhere in the world, writes Jennifer O’Mahony.

When Dakar rises each morning, the first port of call is the boulangerie for a baguette.

While chatting away on phone services provided by Orange, a hungry resident of the Senegalese capital might stop to get cash at local franchises of Société Générale or BNP Paribas, or visit a supermarket: there are Auchan, Carrefour and Casino to choose from.

On the surface, France retains a tight grip on its former colonies: major French telecoms companies, banks and retail giants are ubiquitous in countries such as Senegal, and its political influence remains significant.

And as a result of that colonial history, French remains the official language of Senegal, as well as 19 other countries across Africa.

But when that same Senegalese baguette-hunter is speaking, he might say he is going to the “essencerie” (petrol station) or “dibiterie” (restaurant serving meat), something more interesting is going on.

Africa is changing that most sacred of French cows: its language.

High birth rates

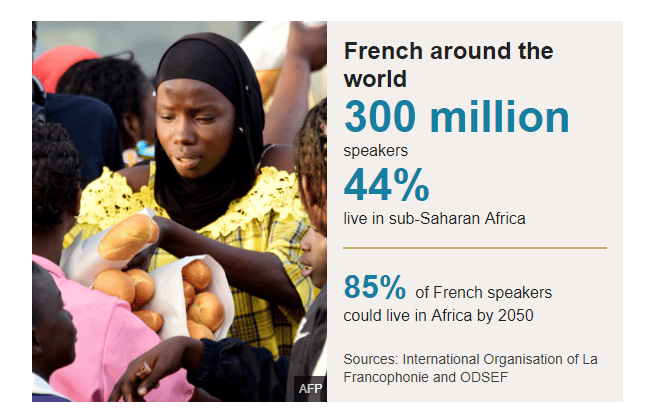

There are 300 million French speakers worldwide today, up almost 10% since 2014, and a recent survey showed that 44% of them live in sub-Saharan Africa.

By 2050, a full 85% of French speakers could live on the continent, according to an estimate by an organisation that monitors statistics on who speaks the language.

Teachers and linguists say this phenomenon is driven by the high birth rate in French-speaking African countries, and to some degree by new language learners in English- and Portuguese-speaking nations.

“The practice of French is increasing on the African continent. It’s a reality driven by demographics, and in West Africa, by countries surrounded by French-speaking neighbours who want to learn the language,” said Céline Desbos, the director of French courses at the Institut Français cultural centre in Dakar.

But French is adapting to the reality of being a second or third language for most of its speakers in Africa, boosting its role as a lingua franca rather than a native language for most.

In March, France’s culture ministry announced that a new digital Francophone Dictionary would be launched, employing a “collective approach” to words from all over the French-speaking world.

French is mixed with local phrases in every African country where it is spoken, creating a rich new vocabulary from the continent that diverges considerably with the French spoken back in “L’Hexagone” (France).

In Ivory Coast, the slang dialect of Nouchi borrows heavily from French and several other languages to create a street patois that has slowly made its way into more rarefied circles.

In 2013, Ivorian President Alassane Ouattara told former Senegalese leader Abdou Diouf “Président, nous sommes enjaillés de toi,” using a Nouchi-French phrase to say “Mr President, we really like you.”

To keep French relevant, organisations such as La Francophonie, a group of 88 French-speaking states and governments, want to encourage the teaching of French alongside local languages, while supporting the adoption of new words.

These days, the local Wolof language is increasingly mixed with French in Senegalese schools, and La Francophonie provides training and support for teachers who sometimes struggle with the rigours of the language of Marcel Proust, the celebrated French writer.

“Children learn to read, write and count in a language, which is not their native language,” explained Francine Quéméner, programme specialist at the French language observatory of La Francophonie.

“Often, teachers have problems with these basics as well, and are not at ease.”

The movement away from scholarly French to a more free-flowing mixture is a phenomenon that has long occurred in Middle Eastern countries such as Lebanon, where Arabic, English and French can often be heard in the same sentence.

The movement in Africa is towards a blend of French-language phrases that are unheard of in France, and the rise of words drawn from local languages.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, for example, a “deuxième bureau” (second office) refers to a mistress rather than an additional place of work, and if one were to “manger quelqu’un” they would not be eating them, but simply beating them in a competition.

‘A continent of polyglots’

For many linguistic observers, this constant evolution calls into question the role of some of the more rigid guardians of the French language.

Chief among them is the Académie Française, a Paris-based institution which issues edicts about French language usage that often run counter to familiar usage.

The Académie decreed just this month that job titles could be made feminine for the first time, so a female minister can now be referred to as “la ministre”, rather than “madame le ministre”.

Many French people have used “la ministre” for years, and Ms Quéméner warned that the Académie risked irrelevance if it could not keep up.

“The French language is not going to wait in all these [African] countries for the Académie to decide before it evolves,” noted Ms Quéméner.

Oblivious to the hauteur of the Académie, French teenagers have long adopted North African phrases that flow from suburbs with high concentrations of immigrants. A typical adolescent conversation might begin with the greeting “wesh?” (what’s up?), before expressing approval for something with “je kiffe”, from “kif”, an Arabic word linked to enjoyment and cannabis.

Other words go back much further, such as “bled”, an Algerian word for village or hometown, which was adopted in colonial times by French soldiers.

Beyond the new vocabulary created in the French language, the uptake of Arabic, English and Mandarin is increasing in Francophone Africa, aimed at maximising study and job opportunities abroad. French is thriving, but on a continent of polyglots.

Meanwhile French-speaking countries such as Rwanda have upgraded English to the status of an official language, and now use it as the language of instruction in schools. Gabon is also considering adding English to its list of official languages.

“The African continent generally speaking is a very plurilingual continent, not just because you have many languages, but because people traditionally speak many languages,” said Souleymane Bachir Diagne, philosophy professor and director of the Institute of African Studies at Columbia University.

Regardless, the pull of France remains strong for many. In 2016-17, 25% of foreign students studying at French universities came from North Africa, and 22% from sub-Saharan Africa.

They bring with them entirely different linguistic backgrounds that will shape the future of French.

“People think of French as just the language of France, and that’s no longer true. We have to change that image,” said Ms Desbos.