Like many other Australian graziers, Matt Bennetto could only start to count the dead after the rain had stopped.

Flying in a helicopter over his sodden cattle station, he was confronted by the “nightmare” of mass cattle losses.

Animals were strewn across pastures which had turned into water and mud.

“We probably flew over 10,000 carcasses that day, just going over my place and the neighbours’,” he told the BBC.

His cattle at Julia Creek were among an estimated 500,000 livestock wiped out when a flood disaster hit northern Queensland earlier this month.

“To see them all dead along the fence lines and in the corners – can you imagine that scene?” he said.

“You spend your whole life trying to breed beautiful animals and then you see something like that. It’s beyond heartbreaking.”

Massive rainfall

Queensland’s cattle industry, worth A$8.6bn (£4.7bn; $6bn), is reeling after the losses in the state’s north.

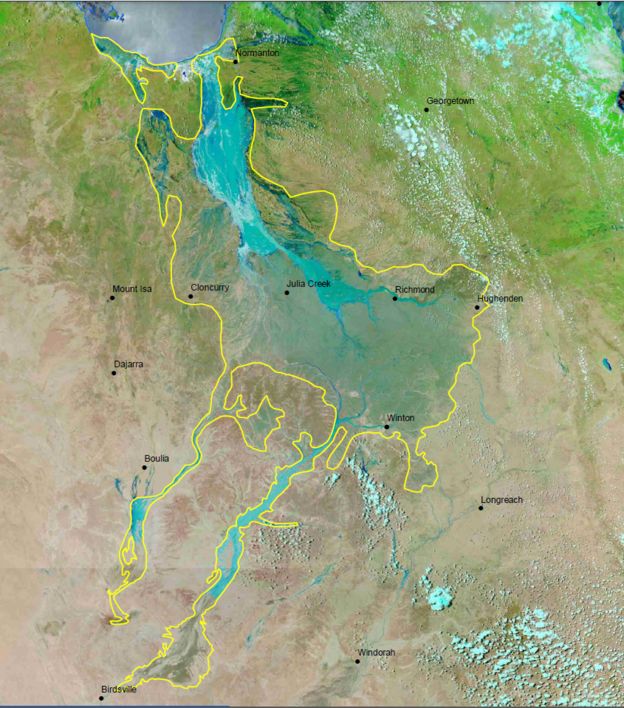

Rain pummelled 13 million hectares of dedicated farming land – an area about the size of England – killing a third of cattle there. The bulk of flooding stretched, in rough terms, between towns Normanton and Winton.

Some areas received three times their average annual rainfall in a week.

At first the deluge was welcomed by farmers, who had sustained their cattle through years of drought.

But as waters rose, the situation quickly turned and led to animals drowning. Many more died from exposure to the elements.

“These cattle are bred in hot, dry conditions,” Mr Bennetto said. “Right before the rain they had gone through a week of over 40-degree [Celsius] temperatures.

“For an animal who can live in such extreme heat, they’re not good at surviving in that cold rain.”

Logistical challenges

The Queensland floods have come in an Australian summer that has been marked by natural disasters.

A number of other mass wildlife deaths have been recorded amid record-breaking heatwaves, and bushfires have destroyed homes in three states.

In the coastal Queensland city of Townsville, floodwaters led to two deaths.

Further west, in the region of the mass cattle deaths, the floodwaters have receded but a crisis remains.

“Producers are attempting to save as many cattle as possible, getting them out of mud and water, and providing them with fodder and medical attention,” said Michael Guerin, head of AgForce, the industry’s peak body in Queensland.

The army has helped bury carcasses and fly hay bales to surviving animals.

Charles Adler from Rural Aid, a charity which organised drop-offs, described it as a logistical challenge.

“Some of these stations are 150km long, so finding alive cattle was a very difficult exercise. And then they’re scattered everywhere in small mobs, so we’re ferrying bales by chopper one at a time,” he said.

He said animals stuck in mud were starving, while others were dying from shock, pneumonia and Three Day Sickness – a bovine fever spread by mosquitoes.

Another grazier, Rachael Anderson, has lost at least 2,000 animals – about half of her herd – at her station in Julia Creek. She said the numbers were continuing to rise.

“We had lots of mothers birth just after the rain, but then die from exhaustion. So I’m hand-rearing 12 calves but there will be more,” she said.

“Lots of people are in the same boat. We are just saving whatever lives we can.”

‘Rebuilding from scratch’

The estimated half a million deaths represent only a portion of Australia’s total cattle industry, which numbers about 27 million.

But for northern Queensland, the toll is immense.

Authorities have put the combined financial loss for about 800 graziers at more than A$5bn. Some farms will not have cash flow for up to three years, AgForce warns.

The region’s industry now has to “rebuild itself almost from scratch”, according to Mr Guerin. He said restocking may take years, while replacing prized “bloodlines” could take decades.

Some graziers find it almost too hard to contemplate. As Mr Adler said: “They’ve struggled for seven years to keep their animals alive in the drought, and now they’re left with the futility of all that.”

Mr Bennetto, who lost more than 70% of his livestock, said he had chosen to suspend operations at his station for now.

“We’re just not in a position to come back right now,” he said. “Maybe in a couple of months, we can get back on our feet and keep going. But I’ve already started a new job this week just so we can afford to pay our bills.”

The government has offered up to A$75,000 in aid for each grazier.

But Ms Anderson said recovery would be “very, very hard”, and in her case take at least 10 years.

“But we are young and resilient,” she said. “We will rebuild. We have to. We have no choice.”