Geraldine Hynes is panicking about the future.

The 63-year-old has been been trying to buy an apartment ever since she was evicted from the home she rented for 32 years – when it was bought by Chinese investors two years ago.

“I want some security in case the same thing happens again,” says Ms Hynes, originally from Ireland. She earns a modest salary as an English teacher, while her Greek husband’s monthly pension was cut from €1,500 (£1,315; $1,690) to €500 during the country’s economic crisis, which began in 2010.

“When we were evicted there were still apartments selling nearby for €100,000. Now I can’t find anything under €250,000. These are Chinese and Russian prices. Not Greek.”

Greece’s financial crisis a decade ago shrank the country’s economy by more than 25% in the following years, but there are finally signs of improvement.

The property market, once completely dead, is on the rise – house prices in Athens rose 3.7% last year.

But this news is causing unease.

The boom appears to be driven by a controversial “golden visa” scheme, in which non-EU citizens receive residency and free movement in the EU’s Schengen zone, in exchange for investing in property.

The worry is that foreign investors are benefiting while ordinary Greeks miss out.

What are golden visas?

Many EU countries including the UK, Portugal and Spain, have golden visa schemes, but Greece has the lowest threshold. Investors receive five-year residency after purchasing €250,000 of property, making the country a new hotspot for foreign buyers.

According to Enterprise Greece – a business promotion body – 9,756 residence permits for investors and their families were issued in 2018 up to the end of November – up from 6,205 in 2017 and 3,695 in 2016.

The biggest market was Chinese buyers, followed by Russians and Turks, with hundreds arriving at Athens airport every week to be driven around by real estate agents.

“There are a lot of companies buying properties from Greeks and reselling to the Chinese,” says Lefteris Potamianos, president of the Athens Real Estate Association, who estimates at least one-third of property sales in the city now go to golden visa investors.

“It affects local people trying to rent properties, who see the prices going up. A lot of properties are going from Greek hands to foreign hands. We can’t control this.”

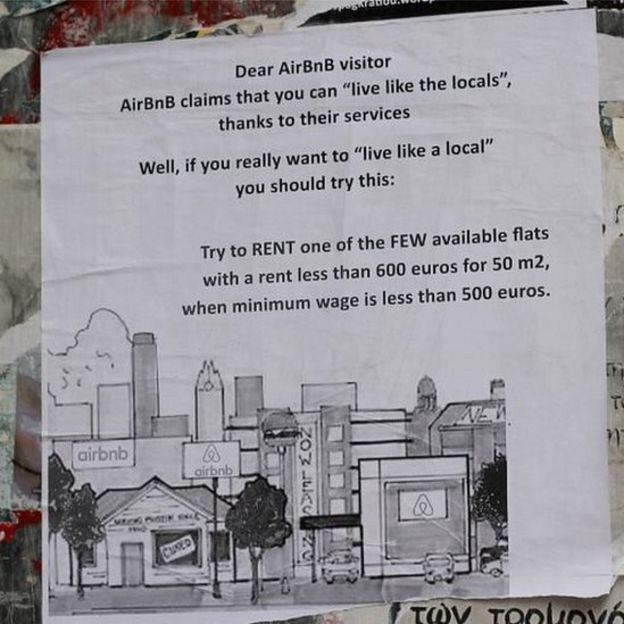

How is this linked to Airbnb?

Because prices in central Athens fell so much during the crisis – down to €1,000 per square metre or less – Mr Potamianos explains that investors will typically purchase three or four apartments in popular tourist spots and rent them out on Airbnb.

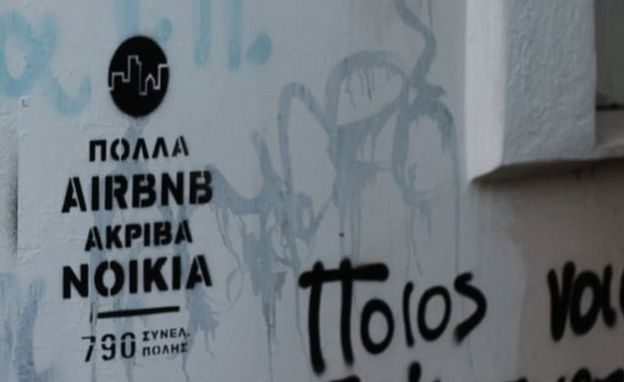

This has caused rents to rise – by 17% last year, according to Greek rental site Spitogatos.

Residents who have benefited from tourist cash, despite Greece’s general economic malaise, are now starting to feel the negative effects.

“Every year I’ve had an increase in visitors, which is good,” says Spyros Bellas, who owns a cafe in Koukaki, a neighbourhood named by Airbnb as one of its top growth areas globally in 2016.

“But now I think it’s gone too far. Rents have doubled to €600, sometimes they’re as much as €1,000. I do not think this reflects the Greek reality. Half of my staff have had to move away.”

His friend George Lafe says his landlord recently increased the rent on his studio apartment from €220 to €400 a month. “If you work in a bar or restaurant here, your salary is only €600-700,” he explains.

Who is benefiting?

Some Athens residents, such as Iro Christodoulaki, have worked the situation to their advantage. The 31-year-old and her boyfriend have bought and renovated three apartments for Airbnb. One recently sold to a Chinese investor for €58,000 – eight times what they paid for it two years ago.

The couple targeted foreign buyers “because they pay more than Greeks” and sold through a Chinese management company to a buyer who has never viewed the apartment.

“During the crisis there were so many abandoned flats that people did not have the money to renovate,” Ms Christodoulaki says. “All our apartments were unliveable when we bought them.”

“We have not taken them off the rental market – we created something new.”

What might happen next?

It’s not just Greeks who are concerned about the volume of golden visas being issued. The EU Commission has warned that the scheme may facilitate organised crime and money-laundering.

The Greek government has introduced tighter controls, yet still plans to expand the scheme to include bonds and shares.

On the streets of Athens, many are calling for far tighter regulation.

“There’s too much freedom right now,” says Mr Bellas. “We need someone to bring rules in, otherwise everything is going to change.”