Last year, a flotilla of 40 fishing boats set sail from northern Sri Lanka with a mission to seize back their island from navy occupation. The BBC’s Ayeshea Perera reports the extraordinary story of how they did this without any bloodshed.

On 23 April, a peculiar sight would have greeted a casual observer standing on the coast of northern Sri Lanka’s mainland, near the village of Iranamata Nagar. They would have seen Catholic priests, women, fishermen, local journalists and civil rights activists crowding on to dozens of tiny motorboats bedecked with white flags and setting determined sail for the island of Iranaitivu.

Their mission: to reclaim the island, their home for many generations and occupied by the Sri Lankan navy for 25 years.

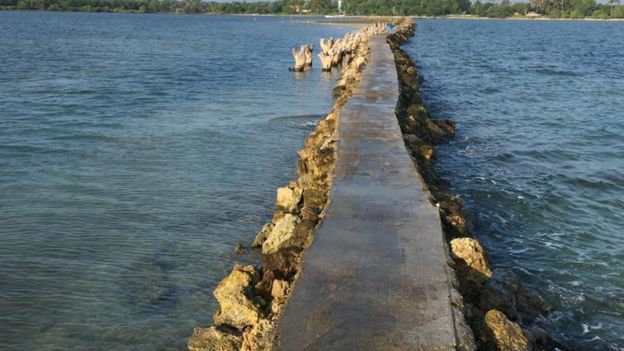

Iranaitivu is really made up of two linked islands – Periyathivu and Sinnathivu. It lies in the Gulf of Mannar, between the southernmost tip of India and the north of Sri Lanka.

It is very much an idyllic paradise.

Aquamarine waters so clear that the fish swimming in it are visible to the naked eye, starfish on unspoiled golden beaches lined with swaying coconut palm fronds, waters so shallow and calm that you can walk about half a kilometre in without it ever reaching your knees… the beauty is almost unreal.

Iranaitivu’s people say they were displaced in 1992 by the navy, who built a base there during the height of the civil war between government forces and the separatist Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). They are not alone – thousands of families in northern Sri Lanka accuse the military of having occupied their lands during the war.

The villagers, who are Tamil, say they were forcibly settled on the mainland in Iranamata Nagar, between the cities of Jaffna and Mannar. They say they have not been allowed to return to the island since. The navy denies this.

Many of those on the boats were women. They told the BBC that they had been “scared” at the thought of potentially confronting armed naval officers, but were determined to do so in any case.

“At the most we expected that we would get some striking footage of a face-off between the naval vessels and our fleet of tiny boats which would help us generate more awareness for the community’s struggle,” said Fr Jeyabalan, one of the priests present on the day.

But to their surprise, there was no stand-off.

A patrol vessel usually docked at the island had been moved to deeper waters, and no other naval ship was visible. The villagers were able to land their boats on the island and walk ashore.

“We were crying, we kissed the beaches. We were home once more and we were never going to leave,” said local community leader Shamin Bonivas.

The group walked over to the dilapidated remains of the island’s church to offer prayer.

It was only then, they say, that some of the naval officers stationed on the island approached. The people informed the officers that they had returned, and were there to stay. The local school teacher produced a file where he had meticulously stored all their land deeds.

Fr Jeyabalan says that after some discussion the navy agreed to let those with the deeds stay on the island for the night, while the others left in the evening. The group spent the day meandering on the beaches, visiting the compounds where their houses once stood and picking coconuts and other fruit from the trees.

A few even ventured into the shallow waters around the island where they were able to easily find fish and prized sea cucumber, which are in high demand in China and elsewhere.

Some villagers set off to recapture some of the cattle they had been forced to abandon, but soon came running back. The cattle were now wild and would not tolerate their former owners’ clumsy attempts to reclaim them.

A month later, government officials who visited Iranaitivu decided to allow the entire village of some 400 families – even those without land titles – to stay. It was an unexpected and heartening victory, but one that went largely unmarked apart from a few articles in the local media.

Everyone in the community can barely believe they have their land back and still cannot explain why the navy let them first land, and then stay on.

The Sri Lankan navy insists that it had never objected to the people of Iranaitivu living on the island after the navy base was built.

The people themselves made the decision to leave “because of troubles with the LTTE and poor habitable conditions”, spokesman Lieutenant Commander Isuru Suriyabandara told the BBC.

But community leaders say that is untrue.

They say that they were not allowed to live on their island despite numerous appeals to various government officials, petitions, and even a peaceful protest on the beach lasting nearly a year.

Documents seen by the BBC also show that various officials, including former chief minister of the Northern Province C Wigneswaran, and the chargé d’affaires of the EU delegation to Sri Lanka, Paul Godfrey, had written to the central government, calling the people of Iranaitivu “displaced” and asking that they be allowed to return to the island.

It has been 10 months since the people of Iranaitivu returned, and the struggle of how they are trying to put their lives back together is clearly visible.

Thatched temporary huts stand next to the remains of hollowed out concrete shells that were once homes. Crude fishing nets are hung out to dry, and people cook on open wood fires with basic implements.

The only signs of modernity are mobile phones, which are charged with tiny solar-powered batteries donated by a well-wisher.

But the signs of development are also there. A few of the old wells have been cleaned up, tiny paths have been cut through the heavy, overgrown brush, and people have begun growing vegetables to supplement their income from fishing. When the BBC visited, the men were busy repairing the church on the smaller island of Sinnativu.

Many of the villagers travel back and forth between the island and their homes in the village of Iranamata Nagar, staying on the mainland for a few days at a time before returning. The island’s school remains in a state of disrepair and so children can’t go to school there.

Since coming back the villagers say that, despite the hardships, their lives are better.

Doras Pradeepan, who is a leader of the community’s fishing co-operative, says that there is much better fishing closer to the island. Now that they can dock their boats there, they spend much less on fuel.

Another woman, Pakiam Kaannikkai, said that after returning to Iranaitivu she was able to earn 70,000 rupees ($380; £300) in just two months thanks to the abundance of fish, crab and sea cucumber around the island.

Villagers live alongside the navy, which says it is in “the national interest” to keep the base there. Iranaitivu, the spokesman said, is an important strategic location to target smugglers and Indian fishermen who illegally cross into Sri Lankan waters.

But the two sides are co-existing peacefully for now, with the navy actively helping people resettle on the island.

The navy has reconstructed the church on the larger island of Periyathivu, provided fresh water supplies to villagers and is building new infrastructure, including pathways.

Locals told the BBC that navy personnel also provide them with machinery and spare parts.

But while the people of Iranaitivu have been able to craft themselves a happy ending of sorts, their struggle to get their land back is depressingly familiar.

It has been almost 10 years since the war ended with the defeat of the Tamil Tigers in May 2009. But the military still occupies 4,241 acres of private land in former conflict areas, according to Sri Lanka’s Secretariat for Coordinating Reconciliation Mechanisms (SCRM).

The military cites both security concerns and strategic importance as reasons for their reluctance to move out.

Several other civilian agitations, including a 700-day protest in front of an army camp in the northern district of Mullaitivu, are still under way.

So will the success of the Iranaitivu villagers’ bold action provide a template for other communities who have been displaced due to military occupation?

Human rights activist Ruki Fernando says it will, though he cautioned that the type of action would depend on the context and the type of community involved.

“If politicians, officials and other institutions don’t deliver justice, and especially if there is no response to complaints, appeals, negotiations or protests, communities have the right to consider non-violent direct action to claim what’s rightfully theirs, as the Iranaitivu community did,” he said.

On the island, the real work is just beginning. Locals say they need significant government help to help them develop the island further. A ferry between Iranamata Nagar and the island has been promised, but they still need to renovate their homes, the local school and the roads around the island. The youth of the island also dream of living there one day.

“Yes we will all return there. This is the home of our ancestors. It is the dream of every single one of us to be buried there,” Mr Bonivas said.