Manufacturing employment in the U.S. is at the same level as 69 years ago

Some food for thought: the U.S. had as many people working in the manufacturing sector in December as it did 69 years ago.

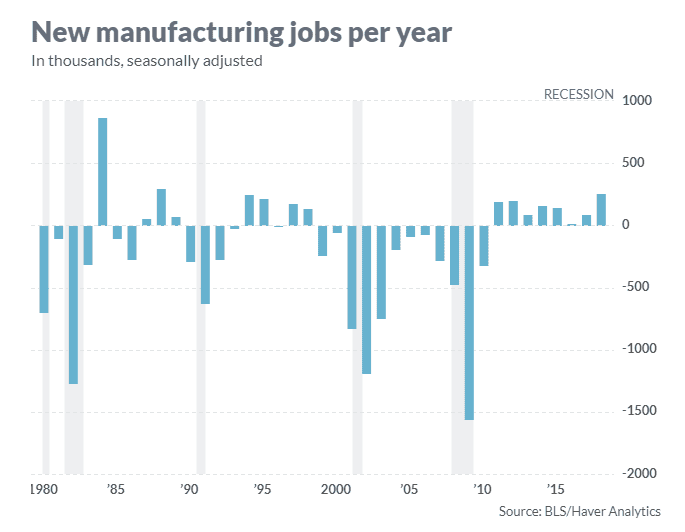

The 32,000 positions added in December took the total number of positions in manufacturing to 12.84 million. In November 1949, there were 12.88 million manufacturing workers, at the end of a sharp recession.

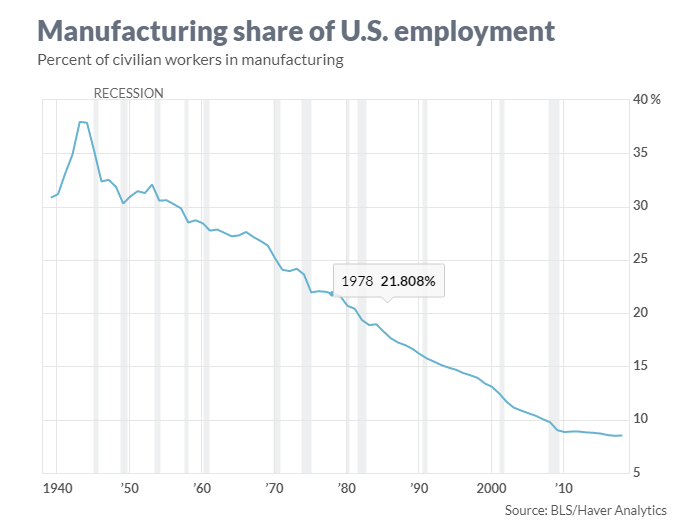

The economy in 1949 was unlike that of the U.S. in 2019 in another way. Then, some 30% of American civilian workers outside the farm sector were in manufacturing; now, that percentage stands at just 8.5%, about as low as it’s ever been.

The hollowing out of America’s industrial base, and the loss of the highly paid jobs for the high-school educated that went along with them, goes some way to reflect the tectonic shifts in U.S. politics that set the stage for the election of President Donald Trump and his brand of populism.

Last year, 264,000 new manufacturing jobs were added, representing the highest number of new workers since 1988. As a percent of the total workforce, manufacturing rose for the first time since 1984.

The White House has not been shy about taking credit, and it’s framing current trade negotiations with China as a way of further increasing those numbers.

“Now, if you give us an opportunity to export more to China, bring those tariff walls down, bring those barriers down, if they give it to us, we will benefit, our trade gap will narrow, our exports will create jobs everywhere, including good-paying and, you know, hard-hat manufacturing blue-collar jobs,” said Larry Kudlow, the director of the White House National Economic Council, during an interview with Fox Business Network on Friday.

Bernard Baumohl, chief global economist for The Economic Outlook Group in Princeton, N.J., said two major things are happening — one, companies are opting to hire workers rather than increase capital expenditure, and two, the White House is actively trying to disrupt global supply chains.

Baumohl said companies have come to the conclusion that the likely 3% growth the U.S. enjoyed last year was a “sugar high.”

With reduced expectations for growth — even with the new incentives to write off depreciation in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act — CEOs have concluded it’s better to meet the additional growth opportunities with new workers than pricier machines.

“Workers are viewed more like inventory,” he says. “If you need them, you can hire them, and if the economy really turns south, you can let them go.”

“CEO have taken a very realistic approach,” he said.

Furthermore, companies already are carrying a record amount of debt, all at a time when interest rates are rising.

As for trade, it’s as much the disruption as the results of the U.S.-China talks that are relevant to companies.

‘What I think companies have done is come to recognize that no matter how it will end, they have seen how vulnerable they are to protectionism,” Baumohl said.

That’s not the only factor that is getting U.S. companies to rely more on domestic supply chains. The spike in the cost of freight containers due to consolidation, and the severe shortage of truckers, has raised transportation costs.