Developing-market stocks haven’t outperformed over the long term

Which produces superior long-term returns: developed-market stocks or those from emerging markets?

It stands to reason that emerging-market stocks should outperform developed ones. Developing economies typically grow at a much faster pace, and it certainly seems plausible that faster economic growth would translate into a faster-rising stock market.

Yet this oft-repeated narrative overlooks the significantly higher risk associated with emerging markets. It’s not unheard of, for example, for an emerging-market country to dissolve, leading investors in that country’s stocks to lose everything. Statisticians accordingly have to exercise great care to make sure that historical databases aren’t guilty of so-called “survivorship bias,” which occurs when the track record of non-survivors is overlooked.

One database of emerging-market equities that is free of survivorship bias comes from Elroy Dimson and Paul Marsh, finance professors at the London School of Business, along with Mike Staunton, director of the London Share Price Database. They presented their findings in a 2002 book “Triumph of the Optimists”, and have been updating their work annually ever since in the Credit Suisse Global Investment Returns Yearbook.

The three researchers succeeded in creating a database for emerging markets back to 1900. They found that emerging market equities have not outperformed developed market equities over the long term. From 1900 through the end of 2017, $1 invested in developed stock markets grew to $12,877, according to their calculations. That same dollar invested in emerging country stock markets grew to just $4,367. On an annualized basis, the difference is between 8.4% and 7.4%.

Moreover, because emerging market equities are significantly riskier, they lagged developed market stocks by an even larger amount on a risk-adjusted basis.

Sure enough, non-survivorship played a big role in emerging market equities’ greater risk. For example, they point out that investors in Russian stocks lost everything in that country’s October 1917 Revolution. “This was a brutal reminder that the very nature of the risk for which [investors] sought a reward means that events can turn out poorly.”

These findings don’t mean that developed markets come out ahead every year, of course. Plus, emerging market stocks may be good bets for other reasons. It may be, as many have argued in recent years, that emerging market equities are far-less overvalued than developed market stocks, especially those in the U.S., and therefore should produce superior returns over the coming few years.

But this valuation-based case for emerging market equities is different than the long-term historical one that is based on the assumption — which Dimson, Marsh and Staunton show is wrong — that emerging market equities eventually will outperform, provided only if investors hang on long enough. Put another way, investing in emerging market equities should be seen more as a market-timing bet rather than an asset-allocation decision.

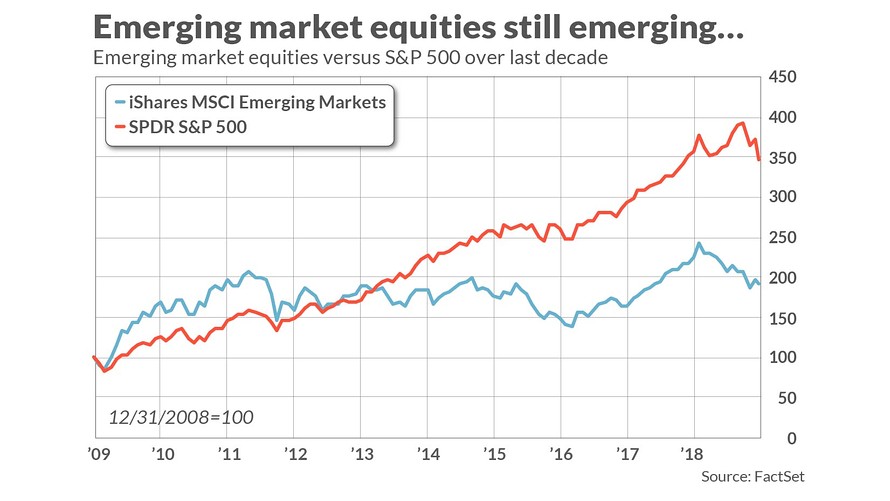

This discussion puts in a new light the last 10 years, during which the S&P 500 SPX, +0.86% has hugely outperformed emerging market equities. (See chart, below). This decade may not be the exception to the long-term rule that many have assumed it to be.

Which emerging market?

To be sure, as I wrote in a recent column, not all emerging country stock markets are created equal. So you may want to choose which emerging market countries to invest in rather than bet on the entire asset class.

Keep in mind that picking the right emerging market to bet on is easier said than done. While there have been some spectacular success stories, there have been nearly as many spectacular failures. Because of survivorship bias, “It is easy to forget the problems that have afflicted once highly promising countries such as Argentina, Nigeria, Venezuela, and Zimbabwe,” as Dimson, Marsh and Staunton point out.