Bear markets generally build up over months while corrections tend to be far sharper

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. — The stock market’s recent correction has been more abrupt than you’d expect if the market were in the early stages of a major decline.

I say that because one of the hallmarks of a major market top is that the bear market than ensues is relatively mild at the beginning, only building up a head of steam over several months. Corrections, in contrast, tend to be far sharper and more precipitous.

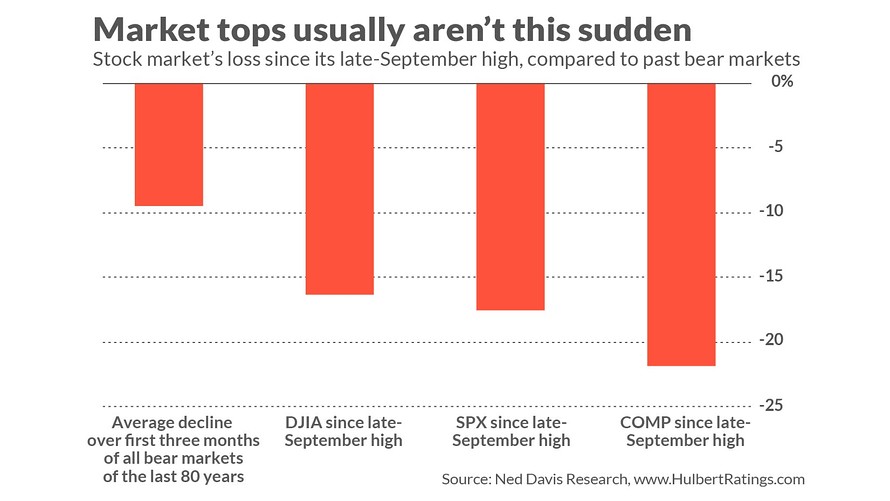

Consider the losses incurred by the Dow Jones Industrial Average over the first three months of all bear markets of the last 80 years. (I used the bear-market calendar maintained by Ned Davis Research.) I focused on this three-month window since that is the length of time since the stock market registered its all-time high in late September. As you can see from this chart, its average loss over these three-month periods was “just” 9.0%.

The stock market’s decline since the all-time highs, in contrast, has been nearly twice as large: The Dow DJIA, -2.91% has skidded 18.7% from its Oct. 3 record close, for example, and the S&P 500 SPX, -2.71% 19.8% from its Sept. 20 record close. The Nasdaq Composite Index COMP, -2.21% has plunged even more: 23.6% from its closing peak in Aug. 29.

There’s a contrarian-analysis-based explanation for why the declines that follow major market tops tend to be more gradual than this: They are usually met with widespread disbelief. Instead, the typical reaction is that those initial declines are good buying opportunities, and the influx of new cash softens the declines that otherwise would occur.

Consider the stock market’s decline over the first three months of the 2007-2009 financial crisis—the worst since the Great Depression. The S&P 500 fell 10.0% over the three months following its top on Oct. 9, 2007, barely even satisfying the semiofficial definition of a correction. The Dow fell 11.1%.

Or take the market’s decline over the first three months after the bursting of the internet bubble. The S&P 500 fell just 5.6%, and the Dow 6.4%.

Corrections, in contrast, have a different contrarian profile. Their sudden and abrupt nature strikes fear in investors’ hearts, thereby setting up the sentiment preconditions for the market to soon climb a Wall of Worry.

This is certainly consistent with what we’ve seen in recent months. As I wrote two weeks ago, rarely over the last 20 years have short-term stock market timers been more bearish than they are currently.

Needless to say, however, there are no guarantees. There were two past major declines of the last 80 years on the Ned Davis calendar that did begin with three-month declines as big as what we’ve experienced recently: the 1987 crash and the decline from July through October of 1990.

But even these exceptions end up proving the rule: Each lasted just three months or so. Contrarians are betting that something similar will be the fate of these declines.