The year 2018 is on course to be the fourth warmest on record, according to the World Meteorological Organization.

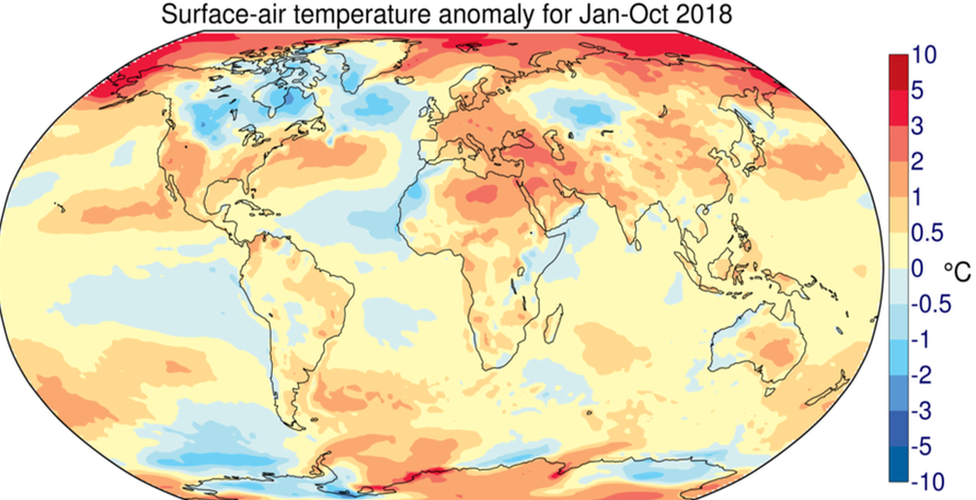

It says that the global average temperature for the first 10 months of the year was nearly 1C above the levels between 1850-1900.

The State of the Climate report says that the 20 warmest years on record have been in the past 22 years, with the 2015-2018 making up the top four.

If the trend continues, the WMO says temperatures may rise by 3-5C by 2100.

The temperature rise for 2018 of 0.98C comes from five independently maintained global data sets.

The WMO says that one of the factors that has slightly cooled 2018 compared to previous years was the La Niña weather phenomenon which is associated with lower than average sea surface temperatures.

Researchers say now that a weak El Niño is expected to form in early 2019 which might make next year warmer than this one.

Regardless of the impacts of these events, scientists say the long-term warming trend has continued in 2018 and they point to sea level rise, ocean acidification and glacier melt as examples of climate change.

“We are not on track to meet climate change targets and rein in temperature increases,” said WMO Secretary-General Petteri Taalas.

“Greenhouse gas concentrations are once again at record levels and if the current trend continues we may see temperature increases 3-5C by the end of the century,” he said.

“It is worth repeating once again that we are the first generation to fully understand climate change and the last generation to be able to do something about it,” said Mr Taalas.

The WMO report says that for the most recent decade, 2009-2018, the average temperature increase was 0.93C above the pre-industrial baseline which is defined as being between 1850-1900. For the past five years, the average was 1.04C.

“These are more than just numbers,” said WMO Deputy Secretary-General Elena Manaenkova.

“Every fraction of a degree of warming makes a difference to human health and access to food and fresh water, to the extinction of animals and plants, to the survival of coral reefs and marine life.

“It makes a difference to economic productivity, food security, and to the resilience of our infrastructure and cities. It makes a difference to the speed of glacier melt and water supplies, and the future of low-lying islands and coastal communities. Every extra bit matters.”

The WMO report highlights some of the significant events of 2018. In the Indian state of Kerala more than five million people were affected by floods. Similarly in Japan, hundreds of people were killed by flooding.

There were also heat waves in large parts of Europe including the UK leading to wildfires in some places including Scandinavia.

In July and August there were numerous record high temperatures north of the Arctic Circle. Helsinki saw 25 consecutive days with temperatures above 25C.

There were major wildfires in the US with the Camp Fire in November claiming the most lives of any fire in over a century in the US.

Greece also had fatalities from fires, while British Columbia broke its record for the most land burned in a fire season.

Scientists involved in preparing the report say that the fingerprint of climate change can now be more clearly seen.

“The warming caused by these greenhouse gas emissions is already clear at the global scale,” said Prof Tim Osborn from the University of East Anglia, who provided some of the data used in the WMO analysis.

“The knock-on effects for our regional climates and for severe weather events are beginning to emerge from the background variability of our weather.”

The WMO State of the Climate report is one of a plethora of recent scientific studies that are designed to inform delegates to next week’s UN climate talks in Poland. Negotiators will attempt to finalise the rule book of the Paris climate pact and to increase their commitments to cut carbon.